What is Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (C-PTSD)?

Understanding the Condition, Symptoms, Risk Factors, and Treatment Options

Alex Penrod, MS, LPC, LCDC — EMDR Therapist | Certified Clinical Trauma Professional II | Austin, TX

Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (C-PTSD) is a condition that can develop in response to prolonged, repeated exposure to traumatic events, particularly those occurring during early developmental years or in situations where escape is difficult or impossible. It differs from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in its causes, symptoms, and treatment needs, and it is especially relevant for survivors of childhood abuse, domestic violence, catastrophic experiences, or captivity.

Just as one rock thrown into a pond will create some ripples, many rocks thrown in or a prolonged storm will create larger waves, crashing into each other in confusing and overwhelming ways. This can make it extremely difficult to regulate emotions on such choppy waters, distorts the way we see ourselves in the reflection, and interferes with our ability to engage with others and maintain relationships when we are just trying to hold on without capsizing.

Organizations such as the International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation (ISSTD) have long recognized complex trauma and developmental trauma disorder as distinct entities requiring more tailored treatment strategies versus those for PTSD. However, C-PTSD was only recently recognized as a diagnosis in the International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11), which came into effect in 2022.

This page provides an overview of the ICD-11 diagnosis of C-PTSD.

C-PTSD Quick Facts

- Complex PTSD results from chronic or repeated trauma, often beginning in childhood.

- Defined by the ICD-11 with added disturbances of self-organization beyond standard PTSD symptoms.

- Common in survivors of abuse, neglect, captivity, or prolonged threat.

- Estimated prevalence: 2–8% in the general population; much higher in abuse survivors.

- Effective care combines EMDR therapy with phased stabilization and relational repair.

- A recent randomized controlled trial of EMDR produced 88% remission among participants who initially met criteria for C-PTSD.

Definition of Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (C-PTSD)

Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (C-PTSD) arises from chronic or long-term exposure to traumatic events which can have profound impacts on the brain and nervous system. Unlike PTSD, which can develop after a single traumatic event, C-PTSD is typically associated with ongoing trauma, such as childhood abuse, severe neglect, physical abuse and domestic violence, human trafficking, or situations of captivity. It involves all the symptoms of PTSD, as well as additional symptoms related to emotional regulation, self-concept, and interpersonal relationships.

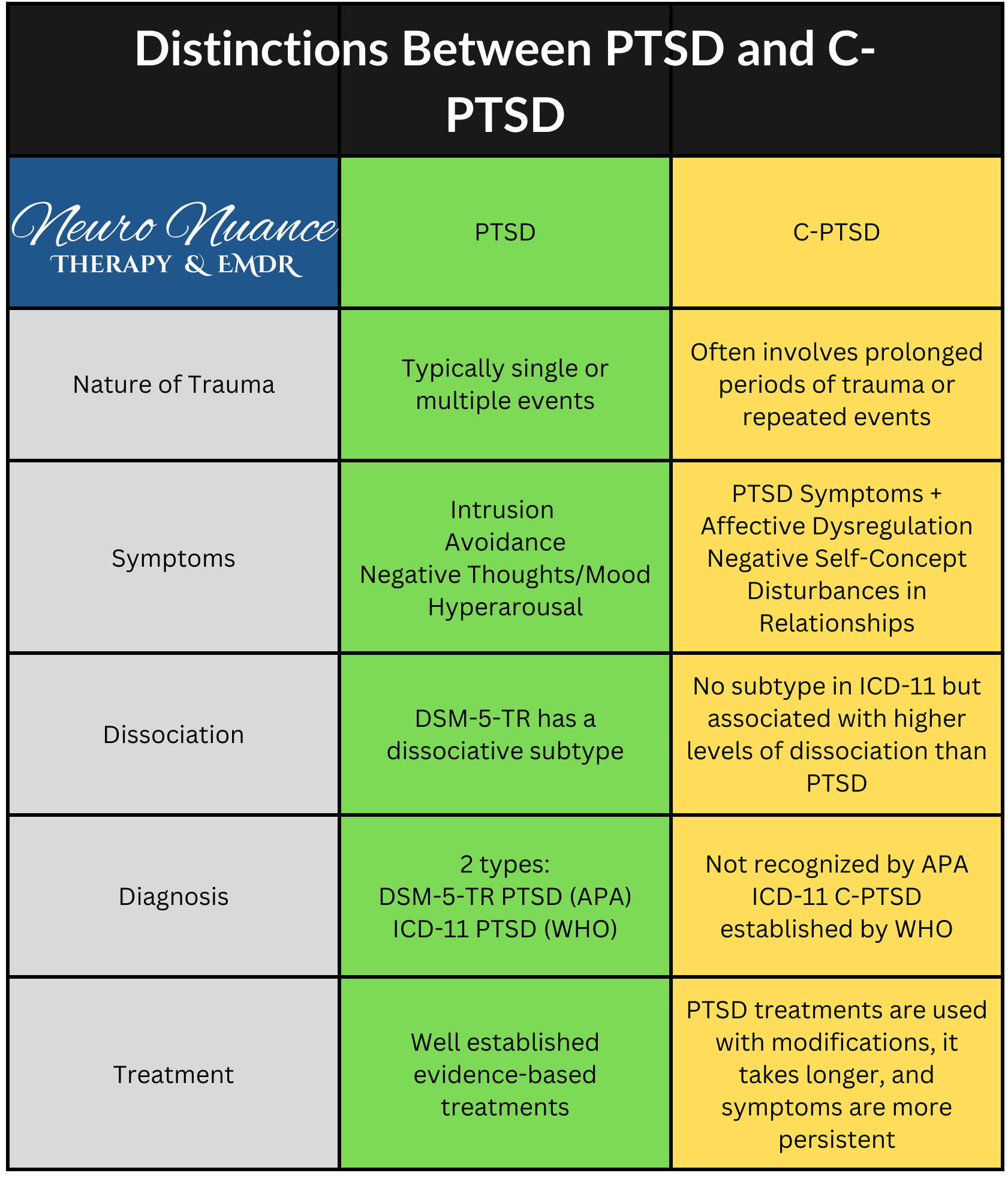

Distinctions Between PTSD and C-PTSD

While both PTSD and C-PTSD arise from traumatic experiences, several key differences distinguish these two conditions:

Nature of Trauma

PTSD: Often results from a single, short-term traumatic event such as a car accident, natural disaster, or assault.

C-PTSD: Typically develops from chronic trauma that occurs over months or years, especially situations of early trauma, child abuse, or within contexts where the victim feels trapped or powerless (e.g., domestic violence, captivity).

Symptom Complexity

PTSD: Symptoms focus primarily on re-experiencing the trauma (flashbacks, nightmares), avoidance behaviors, negative thoughts and mood changes, and hyperarousal.

C-PTSD: Includes all PTSD symptoms, plus additional symptoms such as difficulty with affect regulation, persistent negative self-perception, difficulties in relationships, and feelings of helplessness or hopelessness.

Interpersonal Difficulties

PTSD: May lead to strained relationships due to avoidance and hyperarousal but does not necessarily impact core self-identity.

C-PTSD: Often leads to significant difficulties in forming and maintaining relationships, a pervasive feeling of isolation, and distorted beliefs about oneself leading to a negative self-view (e.g., sense of worthlessness and feelings of shame that go beyond low self-esteem).

Diagnosis and Treatment

PTSD: Diagnosis is more well-established with a clear set of criteria in the DSM-5-TR. Treatment often focuses on trauma-specific therapies.

C-PTSD: Recognized in the ICD-11 but not specifically in the DSM-5-TR, and treatment is more complex due to the need to address developmental and relational trauma aspects.

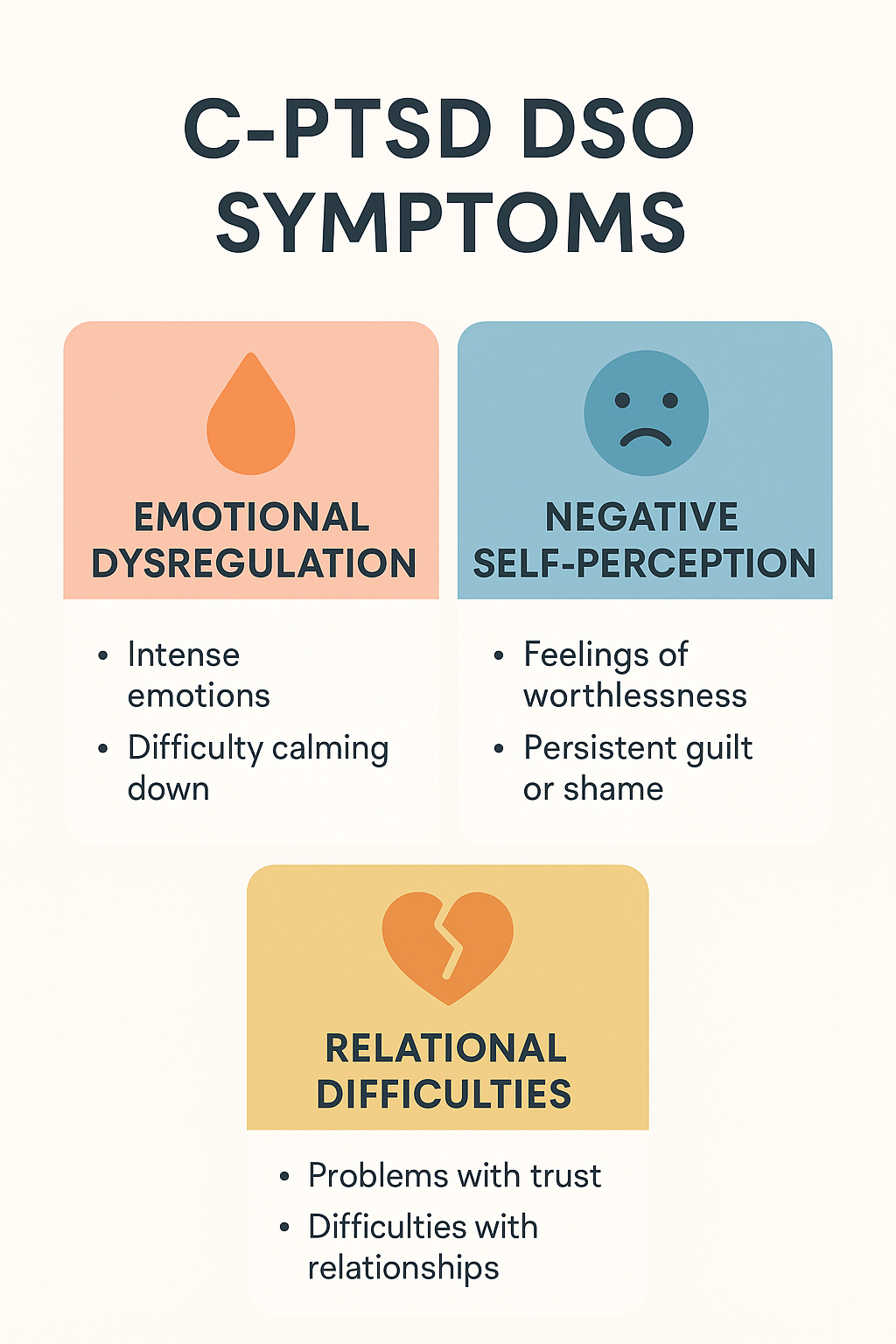

Symptoms of C-PTSD

The symptoms of C-PTSD can be grouped into three core categories beyond those seen in PTSD:

Affective Dysregulation

Persistent difficulty managing emotional responses (e.g., intense strong emotions of sadness, anger, or fear, etc.).

Episodes of emotional numbness or feelings of detachment from one's emotions (e.g., feeling "shut off").

Negative Self-Concept

Deep-seated feelings of worthlessness, shame, or guilt.

Persistent core beliefs of being "damaged" or "different" from others.

Interpersonal Difficulties

Problems in forming and maintaining close relationships.

Difficulty trusting others and feeling emotionally close to others.

Tendency toward social isolation or seeking out relationships that replicate past trauma.

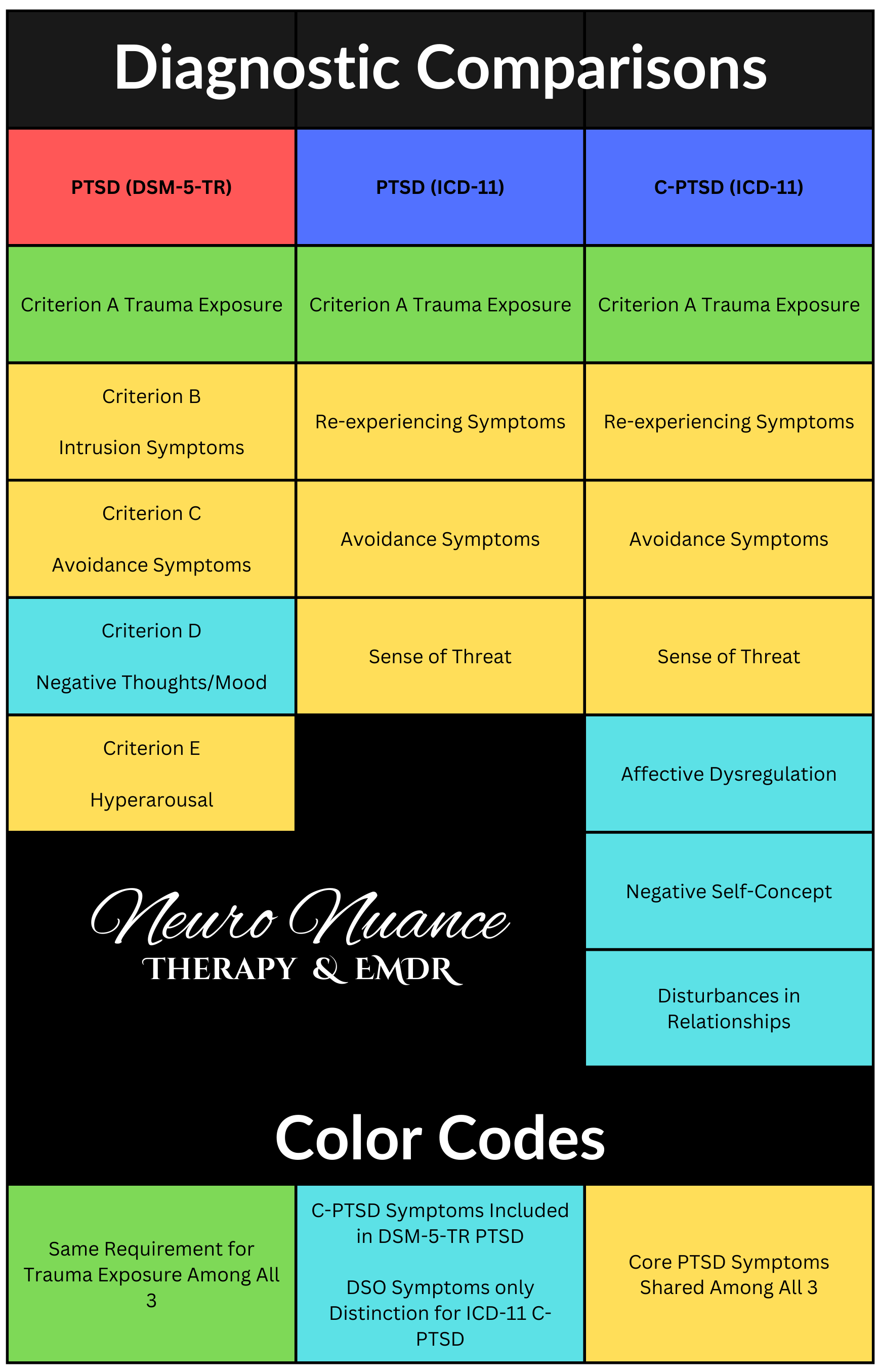

Diagnostic Criteria for C-PTSD

While C-PTSD is not explicitly listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR), it is recognized in the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11). The ICD-11 outlines the following criteria for a mental health professional to diagnose C-PTSD:

Criterion A Event

Just like PTSD, C-PTSD requires that an individual has witnessed, experienced, or been threatened with death, serious injury, or sexual violence.

Core Symptoms of PTSD

All criteria for ICD-11 PTSD must be met (e.g., re-experiencing intrusive memories, avoiding reminders of the trauma, and heightened arousal).

Disturbances of Self-Organization (DSO) Symptoms

In addition to the core symptoms of PTSD, the defining symptoms of C-PTSD are required:

Affective Dysregulation

Severe and persistent difficulty regulating emotions.

Negative Self-Concept

Deep seated feelings of guilt, shame, or worthlessness, often linked to the trauma.

Interpersonal Relationship Difficulties

Problems maintaining healthy, trusting relationships, often resulting in feelings of isolation or conflict.

The duration of symptoms must be at least six months and cause significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. Symptoms must not be the secondary effects of underlying medical issues or substance use, and must not be better explained by another disorder.

Controversy

American psychiatrist, Judith Herman, MD, introduced the diagnosis of C-PTSD in 1992. From the outset it was met with resistance due to skepticism that it truly reflects a separate condition or separate diagnosis. Herman felt that the diagnosis of PTSD didn't fully capture the set of symptoms and complex reactions she observed in survivors of chronic, interpersonal, and childhood trauma. Although it took a long time, her influence did effect change, but not in any kind of coherent way. It resulted in two totally different strategies:

In 2013, The American Psychiatric Association (APA) released the DSM-5, which expanded the diagnostic criteria for PTSD to include symptoms identified by Herman, essentially lumping PTSD and C-PTSD into the same diagnosis by creating room for C-PTSD.

In 2022, The World Health Organization (WHO) released the ICD-11 which created a separate diagnosis of C-PTSD by adding the DSO symptoms (blue) which must be present in addition to meeting criteria for ICD-11 PTSD.

Important to note is that neither approach recognizes a difference in the type of trauma required. The bar for C-PTSD is the same as PTSD regarding what kind of trauma is "severe" enough. The distinctions in both diagnostic systems are focused on the symptom profile of C-PTSD. The United States (APA) and Europe (WHO) both appear to agree that a PTSD diagnosis is reserved for survivors of severe "big T trauma" despite the common misconception that C-PTSD reflects a culmination of "little t traumas" such as emotional abuse.

This makes little difference to trauma therapists who see the damaging effects of “little t traumas” like emotional abuse everyday, but diagnosis is big business and the implications of a lower threshold for diagnosis could cost significant amounts of money for healthcare systems. Read more on this from the National Center for PTSD.

Although it seems Herman was somewhat validated by these diagnostic updates, there is still little consensus in the behavioral health field and we now have two different versions of PTSD making research a bit complex. The American Psychiatric Association and American Psychological Association do not recognize C-PTSD as a diagnosis and some argue C-PTSD reflects PTSD combined with the enduring personality changes seen in borderline personality disorder (BPD). A systematic review of current evidence shows there are distinctions between C-PTSD and BPD, and there is clinical utility of the C-PTSD diagnosis in the ICD system, but not so much for the DSM system.

The good news is that with or without a formal diagnosis, trauma-focused psychotherapists have been recognizing the differences between PTSD and C-PTSD and following Herman's best practices and treatment guidelines for decades. If all of this is making your head hurt, you’re not alone. Therapists would much rather work on helping people heal than split hairs over symptoms and argue with each other. We leave that for the academics, politicians, and businessmen in the field.

Risk Factors for Developing C-PTSD

Several factors can increase the risk of developing C-PTSD following chronic trauma:

Types of Trauma and Duration

Repeated exposure and long-term trauma (e.g., childhood abuse, domestic violence) increases the risk.

Situations where the individual feels trapped, powerless, or unable to escape (e.g., captivity, community violence, trafficking).

Developmental Stage During Trauma

Trauma occurring in early childhood or adolescence, a critical period for emotional, social, and attachment style development, heightens vulnerability. Learn more about the impact of trauma on attachment styles.

Lack of Social Support

Limited support from family, friends, or community following the trauma can increase the risk.

Pre-existing Mental Health Issues

A personal or family history of mental health disorders, such as depression or anxiety, increases susceptibility.

Dissociation During Trauma

Experiencing dissociative states during trauma is linked to a higher risk of developing C-PTSD.

Protective Factors Against C-PTSD

Certain factors can help reduce the risk of developing C-PTSD or mitigate its severity:

Strong Social Support Network

Support from friends, family, and the community can provide emotional and practical assistance. Learn more about building social support for trauma recovery.

Access to Mental Health Resources

Early intervention with trauma-informed care can reduce the risk or severity of symptoms.

Resilience and Coping Skills

Positive coping mechanisms, such as mindfulness, grounding techniques, and emotional regulation skills, can help manage stress and trauma. Learn more about stress management for trauma recovery.

Stable Environment Post-Trauma

A safe and nurturing environment after the trauma can provide a foundation for recovery.

Populations at Higher Risk for C-PTSD

C-PTSD can affect anyone exposed to prolonged trauma, but certain populations are more at risk:

Survivors of Childhood Abuse

Individuals who experienced physical, emotional, or sexual abuse during childhood have a high risk of developing C-PTSD.

Domestic Violence Survivors

Those who experience prolonged intimate partner violence or sexual assault often develop symptoms of C-PTSD.

Refugees and Asylum Seekers

Individuals who have faced prolonged persecution, torture, or displacement may experience C-PTSD.

Human Trafficking Survivors

People subjected to prolonged exploitation or captivity are at significant risk.

Military Personnel and First Responders

While PTSD is common, some military personnel exposed to prolonged combat or captivity may develop C-PTSD.

Prevalence of Complex PTSD (C-PTSD)

Complex PTSD (C-PTSD) is recognized in the ICD-11. Reported rates vary across populations depending on trauma exposure, setting, and diagnostic tools. The following estimates come from peer-reviewed ICD-11 studies using the International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ) or comparable measures.

| Population | Estimated prevalence | Context / notes |

|---|---|---|

| Adolescent survivors of childhood sexual abuse | ~40% | Residential sample of adolescent girls exposed to chronic sexual abuse; ICD-11 / ITQ. |

| Intimate partner violence survivors | ~39–40% | C-PTSD more common than PTSD (~18 %) among IPV survivors. |

| Refugees & asylum seekers | ~36% | Syrian refugees in Lebanon / Jordan (community + treatment settings). |

| Human trafficking / modern slavery survivors | ~41 % (pooled) | Systematic review; PTSD ≈ 14 % for comparison. |

| Military personnel & veterans | ~13 % (community) / ~81 % (treatment-seeking) | Lower in community veterans; much higher in PTSD specialty clinics. |

View sources

- Villalta et al., 2020 – Adolescent girls in residential care after chronic sexual abuse (ICD-11 / ITQ).

- Fernández-Fillol et al., 2021 – Intimate partner violence survivors (C-PTSD 39.5 % vs PTSD 17.9 %).

- Hyland et al., 2018 – Syrian refugees in Lebanon & Jordan (C-PTSD 36.1 %; *Acta Psychiatr Scand*).

- Evans et al., 2022 – Systematic review of trafficking / modern slavery survivors (≈ 41 % C-PTSD).

- Wolf et al., 2014 – U.S. veterans / community sample (≈ 13 % C-PTSD; ICD-11 model).

- Letica-Crepulja et al., 2020 – Treatment-seeking war veterans with PTSD (probable C-PTSD 80.6 %).

- Cloitre et al., 2019 – U.S. general-population study (C-PTSD 3.8 %, PTSD 3.4 %; *Journal of Traumatic Stress*, 32(6)).

Important caveats & limitations

- Setting matters: Treatment-seeking samples show higher rates than community samples.

- Measurement differences: Self-report vs interview and timeframe (point / month / lifetime) affect rates.

- Trauma profile: Prolonged, interpersonal trauma (e.g., chronic abuse or captivity) increases likelihood.

- Cultural context: Rates differ across countries and health-care systems.

- General population baseline: ICD-11 studies estimate roughly 2–8 % of adults may meet C-PTSD criteria worldwide.

Common Co-Occurring Disorders with C-PTSD

C-PTSD often coexists with other psychological disorders and mental health conditions and can lead to the development of other mental health problems, complicating diagnosis and treatment:

Depression

Major depressive disorder is common among individuals with C-PTSD, often linked to feelings of hopelessness or worthlessness.

C-PTSD can make people especially prone to suicidal thoughts due to the intense and enduring negative self-concept.

Depression may also be accompanied by somatic physical symptoms. Learn more about how depression and trauma co-occur in the context of nervous system dysregulation.

Anxiety

Generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and social anxiety frequently co-occur with C-PTSD.

Having an anxiety disorder can be a risk factors for developing a trauma and stressor related disorder.

Substance Use Disorders

Individuals with C-PTSD may use substances as a way to cope with emotional pain and trauma.

The chronic use of substances can make the brain more vulnerable to developing trauma and stressor related disorders. Learn more about the interaction of trauma and substance use disorders.

Dissociative Disorders

Dissociative identity disorder (DID), depersonalization/derealization, or dissociative amnesia can co-occur with C-PTSD, particularly in cases of severe, chronic trauma. Learn more about dissociative disorders and therapeutic approaches to dissociation.

Borderline Personality Disorder

Some individuals with C-PTSD exhibit similar symptoms that overlap with BPD, such as emotional dysregulation, unstable relationships, and impulsivity. However, BPD has differentiating symptoms of its own that can be distinguished.

Evidence-Based Treatments for C-PTSD

Treatment of complex PTSD involves addressing both PTSD symptoms and additional symptoms related to emotional regulation, self-concept, and relational difficulties. Trauma-focused therapy is different from talk therapy in crucial ways highlighting the importance of finding a therapist specialized in trauma. Evidence-based treatments and trauma-focused therapies include:

Phase-Oriented Trauma Therapy

Treatment is often approached in phases, focusing first on establishing safety, stabilizing symptoms, and building coping skills before addressing traumatic memories. Learn more about the phased-approach to trauma therapy.

Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT)

Trauma-Focused CBT can help individuals reframe and process traumatic memories and develop healthier coping mechanisms.

Modifications are often needed for C-PTSD to address developmental and relational trauma aspects.

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR)

EMDR is effective for processing traumatic memories but may need to be adapted for C-PTSD to include preparation phases that focus on emotional regulation and stabilization of dissociative symptoms. Learn more about EMDR therapy.

Prolonged Exposure Therapy (PE)

PE helps individuals desensitize trauma memories through gradually increased exposure, reducing avoidance behaviors and PTSD symptoms.

Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET)

NET involves creating a chronological narrative of a person's life, integrating traumatic experiences with the goal of reducing trauma-related symptoms.

Pharmacotherapy

Medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI’s) can help manage co-occurring symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Other medications may be considered for specific symptoms. Consult with a licensed prescriber for more options.

Recovery Rates for C-PTSD

Recovery from C-PTSD varies widely depending on factors like the severity, duration, and type of trauma, individual resilience, and access to effective treatment. While recovery can be a long-term process beyond what is typical of PTSD, research suggests that with appropriate, trauma-informed care, many individuals can experience significant symptom reduction and improvement in quality of life.

Short-term Recovery: Initial phases of treatment often focus on stabilization and managing acute symptoms, such as flashbacks, anxiety, and emotional dysregulation. During this phase, patients may experience a reduction in immediate distress and develop better coping mechanisms.

Long-term Recovery: Full recovery from C-PTSD can often require a multi-year commitment to therapy, especially for those with deep-seated relational and self-concept issues. However, a recent randomized control trial (2021) produced high rates of remission (88.6%) from C-PTSD within 16 sessions of EMDR or 8 sessions of stabilization followed by 16 sessions of EMDR. After completing treatment, the results were durable at 3 and 6 month follow-ups.

Recovery Maintenance: Even after successful treatment, individuals with C-PTSD may be vulnerable to triggers or stressors that can cause a return of symptoms. Ongoing support, such as periodic therapy sessions or involvement in support groups, can help maintain recovery. Attending to the basics of holistic trauma recovery such as nutrition, exercise, sleep, and using social support are also helpful to maintain symptom relief.

Conclusion

Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (C-PTSD) is a severe, often debilitating condition that requires a comprehensive, trauma-focused approach to treatment. Understanding the unique symptoms, risk factors, and treatment needs is crucial for effective intervention. With early diagnosis, evidence-based therapies, and strong support systems, individuals with C-PTSD can achieve significant recovery, rebuild their lives, and restore a sense of safety, trust, and self-worth.

As a take-away, I’d like to emphasize that although the various authorities in the mental health field can’t seem to agree on C-PTSD, trauma-focused psychotherapists have been recognizing and honoring the differences without the diagnosis for decades. People deserve healing regardless of how academics would like to label them. At Neuro Nuance Therapy and EMDR, PLLC, trauma isn’t pathologized, it’s met with compassion and hope for recovery. To learn more about me and my approach to treating C-PTSD visit my service page on complex trauma therapy or schedule a free 15-minute consultation.

Alex Penrod, MS, LPC, LCDC

Founder | EMDR Therapist | Austin, TX

Last updated November 10, 2025

Disclaimer: This page is meant for educational purposes only and should not be taken as medical or clinical advice for the diagnosis or treatment of any medical condition. Consult with a licensed mental health professional for personalized guidance.

Frequently Asked Questions

-

While PTSD can arise after a single traumatic event, C-PTSD stems from chronic, prolonged trauma (e.g. childhood abuse, captivity, abuse in relationships). C-PTSD includes all core PTSD symptoms, re-experiencing, avoidance, hyperarousal, plus three additional “Disturbances of Self-Organization” (DSO): emotional regulation difficulties, negative self-concept (shame, guilt, worthlessness), and interpersonal relationship challenges.

-

C-PTSD is most often linked to repeated or prolonged interpersonal trauma, especially where escape is difficult or the person feels trapped. Examples include long-term childhood abuse, domestic violence, captivity or trafficking, and situations involving chronic neglect or emotional abuse.

-

Yes. Recovery varies depending on factors like how long the trauma lasted, how early in life it occurred, resilience, and quality of therapy. Treatment typically begins with stabilization (safety, emotion regulation) and progresses into trauma processing and relational healing. Many clients experience meaningful improvement in symptoms, relationships, self-esteem, and quality of life, though some triggers may persist and require ongoing support.

-

Yes, in the ICD-11 (effective from 2022), C-PTSD is formally recognized as a distinct diagnosis. It is not (yet) listed under DSM-5, although the DSM has expanded some PTSD criteria to encompass aspects of chronic trauma.

-

Evidence-based treatments are trauma-informed and often phase-based. Some common approaches include:

EMDR (adapted with stabilization focus)

Trauma-Focused CBT (with modifications for chronic interpersonal trauma)

Prolonged Exposure / Narrative Exposure (adjusted to manage emotional regulation)

Pharmacotherapy (e.g. SSRIs) may support co-occurring anxiety or depression, but should be combined with therapy

Therapy for C-PTSD typically places extra emphasis on emotional regulation, self-concept, and relational healing.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

Cloitre, M., Hyland, P., Bisson, J. I., Brewin, C. R., Roberts, N. P., Karatzias, T., & Shevlin, M. (2019). ICD-11 posttraumatic stress disorder and complex posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States: A population-based study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(6), 833–842. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22454

Evans, E., Ottisova, L., & Bloomfield, M. (2022). The prevalence and presentation of ICD-11 complex post-traumatic stress disorder in modern slavery survivors: A systematic review. European Journal of Psychiatry, 36(2), 104–115. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0213616322000076

Fernández-Fillol, A., Carmassi, C., Belli, E., & Dell’Osso, L. (2021). Complex post-traumatic stress disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder in women survivors of intimate partner violence. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 83, 102458. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34925711/

Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence — From domestic abuse to political terror. Basic Books.

Hyland, P., Vallières, F., Cloitre, M., Ben-Ezra, M., Karatzias, T., Olff, M., Murphy, J., & Shevlin, M. (2018). Are posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex-PTSD distinguishable within a treatment-seeking sample of Syrian refugees living in Lebanon? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53(8), 871–879. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1536-5

Letica-Crepulja, M., Zivcic-Bećirevic, I., Klaric, M., & Franciskovic, T. (2020). Complex PTSD in treatment-seeking veterans with PTSD. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 74, 102263. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7054953/

Melegkovits, E., Blumberg, J., Dixon, E., Ehntholt, K., Gillard, J., Kayal, H., Kember, T., Ottisova, L., Walsh, E., Wood, M., Gafoor, R., Brewin, C., Billings, J., Robertson, M., & Bloomfield, M. (2022). The effectiveness of trauma-focused psychotherapy for complex post-traumatic stress disorder: A retrospective study. European Psychiatry, 66(1), e4. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2022.2346

Nestgaard Rød, Å., & Schmidt, C. (2021). Complex PTSD: What is the clinical utility of the diagnosis? European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 2002028. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.2002028

National Institute of Mental Health. (2022). Traumatic events and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (2021). PTSD: National Center for PTSD. Retrieved from https://www.ptsd.va.gov

van Vliet, N. I., Huntjens, R. J. C., van Dijk, M. K., Bachrach, N., Meewisse, M.-L., & de Jongh, A. (2021). Phase-based treatment versus immediate trauma-focused treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder due to childhood abuse: randomised clinical trial. BJPsych Open, 7(6), e211. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.1057

Villalta, L., Smith, P., Hickin, N., Stringaris, A., & Fonagy, P. (2020). Complex post-traumatic stress symptoms in female adolescents: The role of emotion dysregulation in impairment and trauma exposure after an acute sexual assault. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1708618. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1708618

Wolf, E. J., Miller, M. W., Kilpatrick, D., Resnick, H. S., Badour, C. L., Marx, B. P., Friedman, M. J., & Keane, T. M. (2014). ICD-11 complex PTSD in U.S. national and veteran samples: Prevalence and structural associations. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28(8), 748–756. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4350783/

World Health Organization. (2023). International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11). Retrieved from https://icd.who.int/browse/2024-01/mms/en#585833559