Stress Management for PTSD

Pillar Four of the Six Pillars of Holistic Trauma Recovery

Alex Penrod, MS, LPC, LCDC

EMDR Therapist | Austin, TX

Stress after trauma is not a sign of weakness, it’s the body and mind doing their best to survive overwhelming experiences. When you live with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), ordinary stressors can feel like emergencies, and traumatic reminders can send your nervous system into overdrive or shutdown. Symptoms of PTSD such as intrusive thoughts, intrusive memories, sleep disturbance, sleep problems, and negative emotions are not random, they reflect the way trauma changes how the stress response works. PTSD symptoms can develop after a traumatic event, traumatic experiences such as sexual assault or a natural disaster, and sometimes overlap with acute stress disorder in the short-term period after trauma.

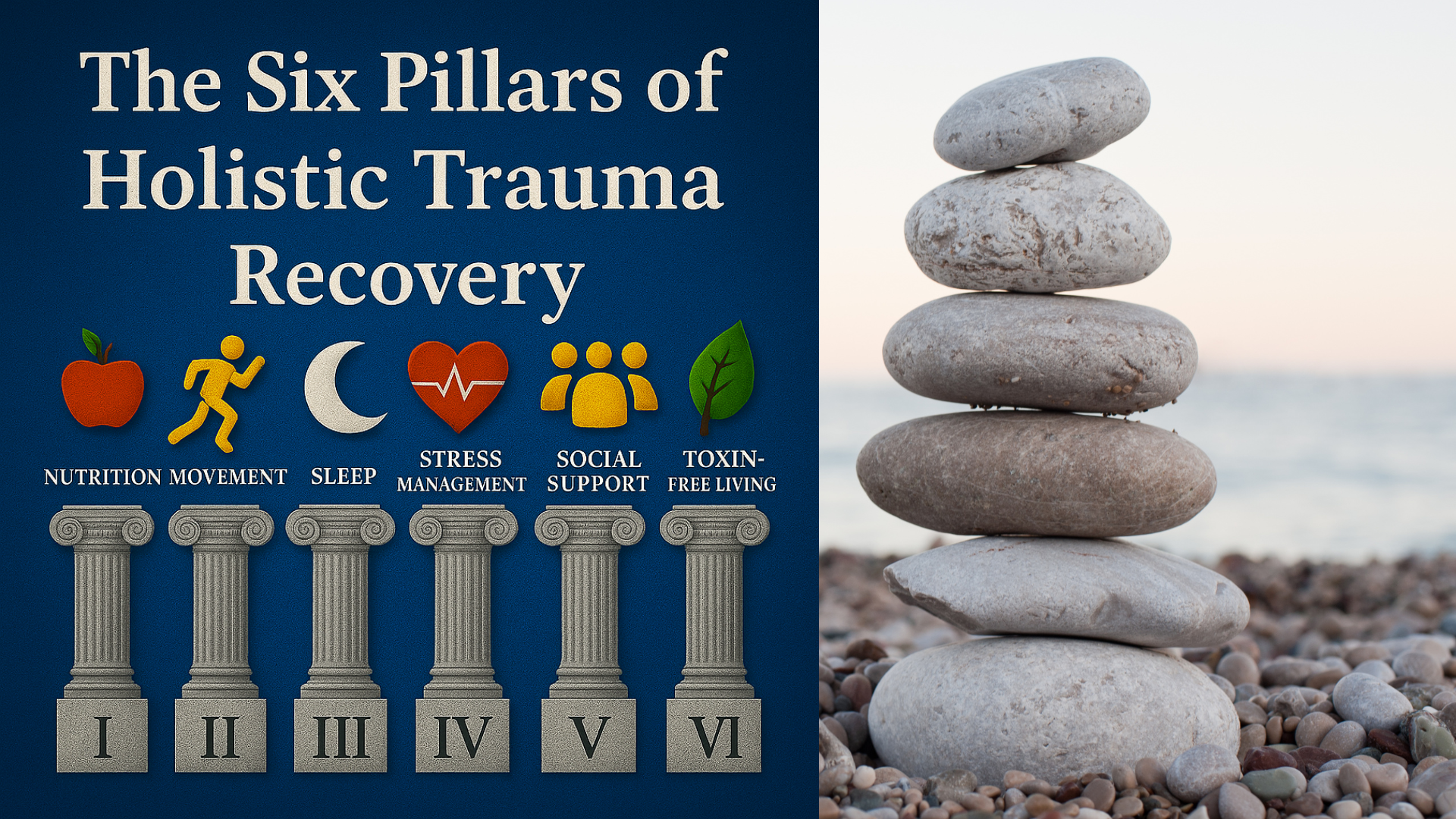

This article is part of my Six Pillars of Holistic Trauma Recovery series, specifically, Pillar Four: Stress Management. Each pillar highlights a lifestyle factor that supports trauma healing in daily life alongside EMDR therapy. As an EMDR therapist, helping my clients heal outside of session is just as important as it is in session. Stress management deserves its own deep dive because it directly affects how the body and mind recover.

In this article, I’ll be using what I call the Adaptive Regulation Model (ARM). This isn’t a formally established treatment model, but a framework I coined to organize well-researched ideas, like allostatic load, the window of tolerance, and mindfulness and values-based coping into one practical system. The goal is to give you a clear map for how stress management can actually work in everyday life with PTSD.

ARM emphasizes three layers: lowering the body’s physiological burden (allostatic load), expanding the usable range of arousal (window of tolerance), and cultivating flexible, compassionate responses (mindfulness, values, boundaries). Rather than thinking of stress management as a single technique, this framework shows how these pieces fit together into a staged plan.

Table of Contents

Allostatic Load: Lower the Baseline

When you live with PTSD, your body often feels like it’s running a marathon it never signed up for. Scientists call the cumulative wear-and-tear of chronic stress allostatic load. It’s the way chronic activation of the stress response (racing heart, tense muscles, disrupted sleep) gradually chips away at physical health and leaves you more vulnerable to illness. Studies have found that a history of stress in childhood and high allostatic load is a risk factor for PTSD and is associated with having a PTSD diagnosis.

The good news: everyday choices can lower the baseline. Simple practices like breathing exercises at six breaths per minute, anchoring your day with consistent sleep and wake times, or getting even ten minutes of brisk physical activity act like small pressure releases on the system. Over time, these reduce cortisol spikes and restore balance. Think of it not as one big fix but as dozens of tiny investments that slowly lighten the load you carry.

Why it matters: Studies show that higher allostatic load scores in people with PTSD predict worse health outcomes and lower quality of life. Lowering this load is one of the most practical forms of stress management you can do outside of therapy.

Window of Tolerance: Expand Your Range

Another key piece of stress management is learning to recognize your Window of Tolerance, the zone where your nervous system can process emotions without tipping into panic or shutting down. Trauma often narrows this window, leaving you bouncing between hyperarousal (anxiety, racing thoughts, anger, startle response) and hypoarousal (numbness, exhaustion, dissociation).

Practical coping skills can help you expand this window over time:

When hyperarousal strikes: slow your breathing, orient to your surroundings by naming five safe things you see, or take a grounding walk outside.

When hypoarousal drags you down: use energizing cues like splashing cold water, light movement, or naming bright colors around you.

When you’re within the window: practice mindful awareness so your system learns what “safe and steady” feels like again.

The aim isn’t to never leave the window, it’s to notice when you’re outside it and have tools to gently guide yourself back in.

Tip: Keep a small card in your wallet that lists “hyper skills” on one side and “hypo skills” on the other. Having a menu ready makes it easier to act in the moment.

To learn more, visit my blog article on Strategies to Regulate Your Nervous System After Trauma.

Mindfulness, Self-Compassion, and Values: Moving With What Matters

While breathing and somatic skills bring your body back into balance, the way you relate to yourself often decides whether stress keeps piling up. Trauma survivors commonly struggle with shame, perfectionism, and blurred boundaries, all of which magnify stress. This is where mindfulness, self-compassion, and values-based living become powerful antidotes.

Mindfulness: Open focus meditation practices can be triggering for trauma survivors because they can create too much space inside for unpleasant things to emerge. Mindfulness adapted for trauma recovery involves anchoring to something pleasant and taking a non-judgmental "noticing" attitude toward unpleasant sensations or negative thoughts, allowing them to be, and letting them pass. Sometimes the less energy you give something, the quicker it moves on.

Self-Compassion vs Shame Spirals: Instead of beating yourself up when symptoms flare, try offering kindness to yourself the way you would to a loved one or family member. Even a 30-second pause to say, “This is hard, and I deserve time to regulate,” can calm the nervous system and interrupt shame’s grip.

Reducing Perfectionism and Workaholism: Constant overdrive fuels allostatic load. Learning to let “good enough” be good enough creates room for rest and resilience. Stress management isn’t about doing more, it’s about doing what restores balance.

Boundaries as Stress Skills: Boundaries aren’t selfish; they’re protective gear. Each time you decline an over-commitment, you free up capacity for healing. Think of boundaries as valves that prevent your system from overheating.

Values-Based Living: Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) principles remind us to ask: “Is this action moving me toward or away from my values?” This two-minute check-in prevents autopilot stress reactions and replaces them with purposeful steps forward.

Spending Time and Positive Emotions: Simple moments, like spending time with loved ones, noticing positive emotions, or enjoying everyday life help counterbalance trauma’s pull toward isolation.

Reminder: “Every ‘no’ to over-commitment is a ‘yes’ to recovery time. Boundaries aren’t selfish; they are protective gear for your nervous system.”

Together, these practices cultivate flexibility, the ability to respond to stress in ways that reduce suffering and restore connection. They don’t erase trauma, but they change your relationship with it, which is where real relief begins.

Evidence-Based PTSD Treatments

For those looking into stress management for PTSD, it’s important to acknowledge that learning to regulate stress is different from the professional treatment of PTSD. There are evidence-based treatments recognized by leading organizations like the American Psychiatric Association, the American Psychological Association, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the Department of Defense.

These include Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT), Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT), Prolonged Exposure Therapy (PE), Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), and trauma-focused psychotherapy. Group therapy and family therapy are also sometimes recommended. Medications like selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are commonly used as well.

But here’s the key: while these therapies are often considered first-line treatment options, stress management strategies like the ones outlined in this article play a crucial complementary role. They help clients lower baseline stress, widen their Window of Tolerance, and build everyday resilience so that therapy, if and when it’s pursued, can be more effective.

You don’t need to be in therapy to benefit from these skills. Practicing self-compassion, setting healthy boundaries, getting regular sleep and movement, and learning grounding strategies all reduce the overall load on your system. These holistic practices give you agency in your daily life, whether or not you’re engaged in formal professional treatment or mental health treatment.

Key takeaway: Evidence-based therapies treat the root of PTSD. Holistic stress skills support recovery every single day. One does not replace the other—they work best together.

The Staged Plan

Stress management for PTSD is most sustainable when it follows a phased process rather than a random grab bag of techniques. The Adaptive Regulation Model (ARM) lays this out in four progressive stages:

Phase 1: Stabilize (Short-Term Relief)

The first priority is lowering the body’s stress load and creating a basic sense of safety. Focus on simple, repeatable habits: steady breathing exercises, consistent bed and wake times, and grounding skills for hyper- or hypoarousal. Even small wins, like one extra hour of sleep or three minutes of paced breathing, begin to lighten allostatic load.

Phase 2: Expand (Building Capacity)

Once stability is in place, the next step is to expand the Window of Tolerance. This means practicing awareness of when you’re above or below the window and gently applying tools to return inside it. Somatic practices, brief movement, and supportive social contact all help stretch the system’s resilience. Expansion isn’t about pushing, it’s about gentle stretching of capacity.

Phase 3: Integrate (Living with Flexibility)

This is where the focus shifts to how you relate to yourself and the world. Self-compassion practices reduce shame. Setting boundaries protects energy. Letting go of perfectionism reduces chronic overdrive. ACT-style values work guides daily choices. Integration means stress is no longer just managed, it becomes an opportunity to practice alignment with what matters most.

Phase 4: Maintain (Long-Term Resilience)

Stress spikes are inevitable, but with a toolkit in place, they become manageable rather than overwhelming. Maintenance involves weekly check-ins, refreshing skills, and leaning on supports when needed. This stage is about making recovery a lifestyle, not just a crisis response. Relapse into old habits is normal; the key is recognizing it quickly and re-engaging with your skills.

Tip: Think of the plan like a training program. Stabilize your foundation first, expand your capacity, integrate flexibility into everyday life, and maintain with regular tune-ups.

Quick Self-Assessment & Planner

Stress management becomes real when you can track it in everyday life. A simple self-assessment helps you notice patterns and decide which skills to use. Try rating yourself once a week across six areas:

Sleep: How consistent and restful were your nights? (0 = very poor, 5 = very good)

Movement: Did you engage in any physical activity, even brief walks or stretching? (0–5)

Stress Management Skills: How often were you able to regulate hyperarousal when feeling activated? (0–5)

Presence/Engagement Skills: How often were you able to regain presence and engagement when feeling shut down? (0–5)

Boundaries/Values Actions: How often were you able to say no when needed or take small steps aligned with your values? (0–5)

Connection/Social Support: How often were you able to reach out to supportive people or spend time with loved ones? (0–5)

How to use it: Add up your scores each week. A higher total means you’re managing stress more effectively. A lower score doesn’t mean failure, it’s simply feedback on where to focus next week.

Tip: Print this table. The act of checking in builds awareness, which itself is a stress-regulation skill.

Example of Stress Tracking

| Day | Sleep Quality (0–5) | Movement / Physical Activity (0–5) | Stress Regulation (0–5) | Presence / Engagement (0–5) | Boundaries / Values Actions (0–5) | Connection / Social Support (0–5) | Daily Total | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mon | ||||||||

| Tue | ||||||||

| Wed | ||||||||

| Thu | ||||||||

| Fri | ||||||||

| Sat | ||||||||

| Sun | ||||||||

| Weekly Average |

Research, In Plain Language

You're probably not looking for dense academic language, but it helps to know that the ideas in this framework are backed by strong evidence. Here’s what the research shows:

Allostatic Load and Stress Physiology

Researchers describe allostatic load as the body’s cumulative wear-and-tear from repeated stress. Reviews show that people with PTSD often carry higher allostatic load scores, which predict worse health outcomes. Recent studies also highlight the role of heart rate variability (HRV): lower HRV is linked with greater PTSD symptom burden, and practices like paced breathing may help restore balance. Clinical trials and systematic review evidence support these links.

Window of Tolerance and Arousal Regulation

The concept of the window of tolerance, introduced by Daniel Siegel and expanded by trauma specialists like Pat Ogden, remains central to understanding why trauma narrows our emotional range. Current research integrates this model with findings on brain circuits, showing how hyper- and hypoarousal disrupt learning and connection. This validates skills like grounding, orienting, and titrated exposure as practical ways to “stretch the window.”

Mindfulness and MBSR

A 2024 meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials found that Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) produces moderate improvements in PTSD symptoms. Other reviews show mindfulness practices enhance emotion regulation, though program quality varies. The takeaway: mindfulness isn’t a cure-all, but when practiced consistently, it’s a useful adjunct that improves daily coping.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)

ACT helps trauma survivors shift from avoidance to acceptance and take small steps guided by values. A recent meta-analysis across trauma-exposed samples found moderate, significant reductions in trauma-related symptoms compared with control groups. This supports using values and diffusion exercises as core stress management strategies.

Clinical Guidelines

The Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense guidelines (2023/24) note mindfulness as an adjunctive option and emphasize trauma-focused psychotherapies as first-line care. The American Psychiatric Association and American Psychological Association similarly highlight evidence-based therapies like CPT, PE, and EMDR. These Clinical Practice Guideline documents, along with the Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, show where stress skills fit in the bigger picture, but the focus of this article remains on practical, everyday strategies.

Bottom line: The science confirms what many trauma survivors know from experience, lowering baseline stress, expanding the window of tolerance, and cultivating flexible coping aren’t optional extras. They’re evidence-informed practices that make healing possible inside and outside therapy.

Conclusion

If you’re navigating PTSD, you don’t have to do it alone. These strategies are a starting point, but working with a trauma-informed mental health professional can help you integrate them more deeply. At Neuro Nuance Therapy and EMDR, PLLC, I specialize in helping people integrate stress management skills into an overall strategy for treating PTSD. If your curious about EMDR therapy in Austin, TX or virtually across Texas, schedule a free 15-minute consultation to learn more about your options.

Alex Penrod, MS, LPC, LCDC

EMDR Therapist | Founder, Neuro Nuance Therapy and EMDR, PLLC | Austin, TX

Last Updated October 5, 2025

Disclaimer: This article is meant for educational purposes only to provide examples of stress management. It is not intended to diagnose or treat any condition and should not be taken as medical or clinical advice. Seek the assistance of a medical or clinical professional for more personalized advice and treatment for PTSD.

Frequently Asked Questions

-

Stress management in PTSD means more than relaxing, it means lowering your baseline stress burden, widening your tolerance for stress, and cultivating flexible coping skills so that everyday pressures don’t overwhelm you.

-

Allostatic load is the cumulative “wear and tear” your body carries from chronic stress. In people with PTSD, elevated load can worsen health, fatigue, and symptom severity. Reducing it is a foundational step toward recovery.

-

The Window of Tolerance is your optimal zone of arousal where you can think, feel, and act without shutting down or flooding. Trauma often narrows this window; stress management aims to gently expand it so you can better regulate emotions.

-

If hyperaroused: slow your breathing, ground yourself by naming safe things around you, take a short walk, or orient your senses.

If hypoaroused: use gentle movement, cold stimulation (splashing water), or light sensory input to help re-engage.

These are tools to guide you back into your optimal zone.

-

Mindfulness helps you notice internal states without judgment, boundaries protect your capacity, and self-compassion interrupts shame cycles. Together, they shift your relationship with stress and help you respond rather than react.

-

No. You can practice many stress management techniques on your own. That said, combining these skills with trauma-informed therapy (EMDR, CPT, PE, etc.) often leads to deeper, more sustainable healing.

Learn More About Holistic Trauma Recovery

References

American Psychological Association. (2017). Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/ptsd.pdf

Carbone, J. T., Dell, N. A., Issa, M., & Watkins, M. A. (2022). Associations between allostatic load and posttraumatic stress disorder: A scoping review. Health & Social Work, 47(2), 132–142. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hlac001

Corrigan, F. M., Fisher, J. J., & Nutt, D. J. (2011). Autonomic dysregulation and the window of tolerance model of the effects of complex emotional trauma. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 25(1), 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881109354930

Department of Veterans Affairs & Department of Defense. (2023). VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder (Provider summary). https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/VA-DoD-CPG-PTSD-Provider-Summary.pdf

Fetzner, M. G., & Asmundson, G. J. G. (2015). Aerobic exercise reduces symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 44(4), 301–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2014.916745

Lang, A. J., Strauss, J. L., Bomyea, J., Bormann, J. E., Hickman, S. D., Good, R. C., & Essex, M. (2017). Randomized controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy for distress and impairment in OEF/OIF/OND veterans. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 9(2), 194–203. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000127

Luo, X., Che, X., Lei, Y., & Li, H. (2021). Investigating the influence of self-compassion-focused interventions on posttraumatic stress: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 12(12), 2865–2876. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-021-01732-3

Molnar, D. S., Lisk, S., & Carreiro, A. V. (2020). Perfectionism and perceived control in posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 61(5), 634–642. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12650

Pfaltz, M. C., & Schnyder, U. (2023). Allostatic load and allostatic overload: Preventive and clinical implications. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 92(5), 279–282. https://doi.org/10.1159/000534340

Polusny, M. A., Erbes, C. R., Thuras, P., Moran, A., Lamberty, G. J., Collins, R. C., Rodman, J. L., & Lim, K. O. (2015). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for posttraumatic stress disorder among veterans: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 314(5), 456–465. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.8361

Rosenbaum, S., Vancampfort, D., Steel, Z., Newby, J., Ward, P. B., & Stubbs, B. (2015). Physical activity in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 230(2), 130–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.10.017

Schneider, M., & Schwerdtfeger, A. (2020). Autonomic dysfunction in posttraumatic stress disorder indexed by heart rate variability: A meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 50(12), 1937–1948. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329172000207X

Wang, J.-Q., Yin, S., & Zhang, M. (2024). Effects of acceptance and commitment therapy on trauma-related symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001785