Rest to Rewire: Sleep and PTSD Recovery

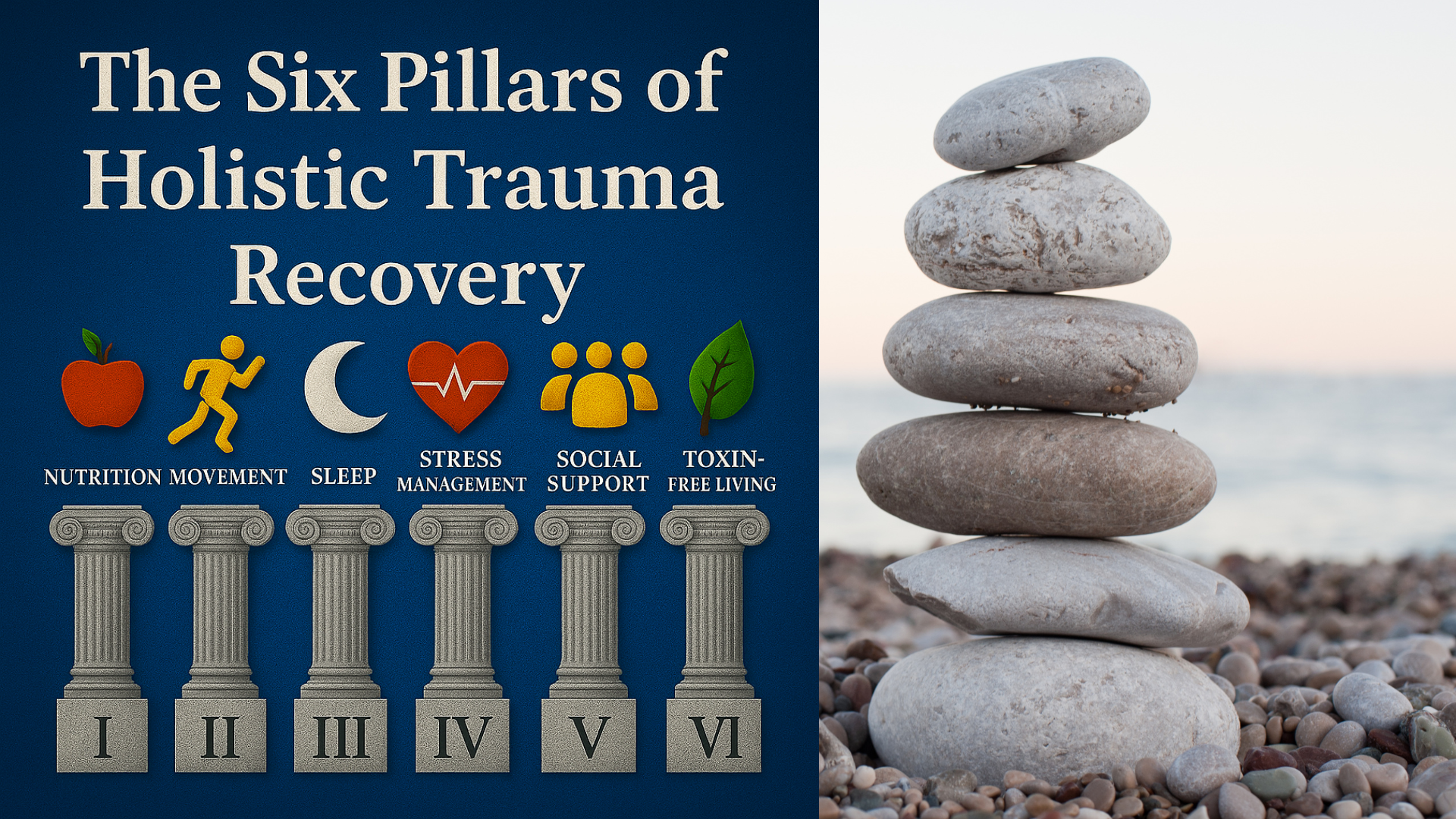

Pillar Three of the Six Pillars of Holistic Trauma Recovery

Alex Penrod, MS, LPC, LCDC

EMDR Therapist | Founder, Neuro Nuance Therapy and EMDR, PLLC | Austin, TX

When your nervous system never gets to rest, healing remains out of reach.

When we think of trauma recovery, we often picture therapy sessions, EMDR, mindfulness, or other active healing strategies. But one of the most powerful, and most disrupted, tools for recovery is something we often take for granted: sleep.

Sleep is Pillar Three in the Six Pillars of Holistic Trauma Recovery, and for many trauma survivors, it’s one of the first casualties after a traumatic event. Research from the National Center for PTSD suggests that between 70–90% of individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder experience significant sleep problems, including difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, nightmares, or waking in a state of high alert. For trauma survivors, the night can feel less like a place of rest and more like a battleground.

Before we dive in, I want to share why I’m so invested in this topic. As a trauma therapist specializing in EMDR therapy in Austin, TX, I’ve seen firsthand how restoring sleep quality can transform an individual’s recovery process. Drawing from research in sleep medicine, neuroscience, and clinical practice, we’ll explore how trauma affects sleep, why it matters for PTSD treatment, and the trauma-informed strategies that can help you reclaim the night.

Table of Contents

How Does Trauma Disrupt Sleep?

Sleep problems are among the most commonly reported PTSD symptoms, disrupting sleep in the following ways:

Difficulty falling asleep (increased sleep onset latency)

Waking frequently through the night

Vivid nightmares or night terrors

Sleep fragmentation and poor sleep efficiency

Daytime sleepiness and fatigue

Sleep-disordered breathing or increased limb movements

These symptoms reflect an overactive stress response system, particularly the sympathetic nervous system, that remains engaged long after the traumatic experience has passed. For individuals with combat exposure, sexual assault, or early childhood trauma, the nervous system learns to associate vulnerability with danger. Sleep, by its nature, requires a kind of surrender that no longer feels safe.

This state of hyperarousal leads to sleep disruption, shortened REM sleep, and increased REM density, the brain's failed attempt to discharge overwhelming emotional material while the body remains on edge. Left untreated, these disturbances not only interfere with sleep quality, but also reinforce PTSD severity and worsen psychiatric symptoms over time.

What is Sleep Architecture?

Sleep architecture is the pattern and organization of the different sleep stages: light sleep (N1-3), deep slow-wave sleep, and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, that make up a healthy sleep cycle. Each stage supports critical functions like physical repair, emotional regulation, and memory consolidation. In trauma survivors, especially those with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), this architecture is often disrupted by nightmares, difficulty falling asleep, and frequent awakenings.

These disturbances reduce sleep quality, impair the role of sleep in PTSD recovery, and interfere with processes like REM-related extinction learning. This is one of the reasons even those who get an adequate duration of sleep (7-9 hours) can still wake up feeling fatigued and not well rested.

How Does PTSD Disrupt Sleep Architecture?

PTSD disrupts sleep architecture in observable ways demonstrated by polysomnographic studies of brain waves. Although there are trends across studies involving light, deep slow wave, and REM sleep, individual differences and other factors interfere with identifying a definitive “PTSD signature” sleep pattern. The following table summarizes key functions of each sleep stage, how trauma can disrupt them, and what research says about the impact on PTSD symptoms.

The Vicious Cycle: PTSD Makes Sleep Worse and Vice Versa

It’s a two-way street. Poor sleep doesn't just result from PTSD, it may predict its development. Research shows that sleep disruption immediately following a traumatic event is a significant risk factor for developing post-traumatic stress disorder. In part, this is because the brain is unable to engage in memory consolidation during REM sleep, a process that supports extinction learning, the neurological mechanism through which we unlearn conditioned fear responses.

When REM and slow-wave sleep are impaired, the brain struggles to integrate traumatic experiences into long-term, emotionally regulated memory. Instead, traumatic memories remain raw, disorganized, and easily reactivated by reminders. Over time, this creates a self-reinforcing feedback loop where poor sleep increases emotional reactivity, and emotional reactivity prevents quality sleep.

Nightmares, intrusive thoughts, daytime hypervigilance, and chronic fatigue all feed into this loop, decreasing quality of life and interfering with the sleep cycle. And sleep deprivation can increase the occurrence of intrusive thoughts, flashbacks, and reduced emotion regulation during the day.

This makes disturbed sleep not only a symptom of PTSD but a contributor to increased PTSD symptom severity, further highlighting the role of sleep in a foundation of healing. There are several evidence-based treatment options to choose from. We’ll explore those after looking at some common sleep patterns observed in PTSD.

Table: Common Sleep Patterns Observed in PTSD

Sleep architecture refers to the structure of different sleep stages: light sleep, deep slow-wave sleep, and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep throughout the night. Research shows that people with posttraumatic stress disorder often experience disruptions in these patterns, but there is no single “objective signature” of PTSD sleep disturbance that sets it apart from other mental health conditions. Still, certain features show up frequently across studies. This table summarizes those common patterns, what they mean, and where the findings come from.

| Sleep Pattern | What the Research Shows | Why It Matters | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Difficulty falling/staying asleep (insomnia, fragmentation) | Over 70% of people with PTSD report these symptoms. | Persistent hyperarousal and disrupted rest decrease recovery potential. | So et al., 2023 |

| Reduced total sleep time & sleep efficiency | Meta-analyses show lower total sleep and efficiency in PTSD vs. controls. | Less restorative sleep means more daytime fatigue and emotional reactivity. | Zhang et al., 2019 |

| Reduced slow-wave sleep (deep sleep) | Meta-analytic findings show reductions accross studies. | Deep sleep is when the body repairs; its disruption reduces physiological resilience. | Zhang et al., 2019 |

| Decreased REM Sleep Percentage | Studies that include people under 30 show decreased REM sleep percentages. | May relate to difficulty processing and consolidating trauma memories | Zhang et al., 2019 | Greater REM Sleep Density | Meta-analytic findings have shown the intensity of REM sleep to be increased. | May relate to jolting awake and increased movement. | Koffel et al., 2016 |

Are there Trauma-Informed Sleep Interventions That Work?

The good news: sleep issues can heal, when the whole system is supported.

Trauma-informed treatment plans often incorporate a combination of behavioral, cognitive, environmental, and somatic strategies. Among the most evidence-based approaches are:

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I)

CBT-I is considered a first-line intervention by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and the Department of Veterans Affairs for trauma-related insomnia. It includes coping strategies and techniques such as:

Stimulus control (retraining the brain to associate bed with sleep)

Sleep restriction (consolidating fragmented sleep)

Cognitive restructuring (challenging trauma-related beliefs about sleep)

Relaxation techniques (breathing, progressive muscle relaxation)

CBT-I is often effective even in complex PTSD cases and can be combined with trauma-focused therapies like EMDR to address underlying trauma. CBT-I is often provided by a broader range of healthcare professionals vs niche trauma therapy which is a less accessible specialty.

Imagery Rehearsal Therapy (IRT)

IRT helps reduce nightmare frequency and distress by allowing clients to re-script recurring nightmares in a safe, controlled therapeutic setting. This approach can be particularly helpful for survivors of nightmare disorder, sexual assault, or combat trauma, and is supported by clinical trials and systematic reviews. It's important to remember that sleep interventions serve as a compliment to PTSD treatment and do not directly resolve or treat PTSD on their own.

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) and Exposure Therapy

EMDR is an evidenced-based treatment for PTSD that helps process the traumatic memories that often underlie nightmares and chronic sleep problems. It's supported by over 30 randomized controlled trials showing effectiveness for treating PTSD. Many clients report improvements in sleep quality after EMDR, especially when nightmares are linked to unprocessed trauma. Reprocessing these memories reduces the need for the brain to revisit them during REM sleep.

However, even after undergoing trauma-focused therapy, many trauma survivors continue to report insomnia, highlighting the value of combining trauma-focused therapies with therapies like CBT-I that target insomnia specifically.

EMDR can also target the fear of sleep itself, the part of the psyche that associates sleep with vulnerability, flashbacks, or helplessness. There are several other evidenced based therapies for PTSD to choose from.

Are there Medications for Sleep and PTSD?

Although there are only a few medications specifically approved by the FDA for PTSD, some medications are used off-label to address sleep disturbance in PTSD by reducing nightmares. There are many medications for sleep specifically, but this is not as straightforward as it sounds. There are side-effects, trade-offs, and when considering the overall picture of PTSD and mental health symptoms, it is always best to consult with a psychiatric professional trained to consider these factors before zeroing in on sleep specifically.

I advise all my clients to give as much information as possible to their prescriber so they don’t become laser focused on one symptom and miss the full picture. Sleep architecture is complicated and you want to provide as much information as possible to make the decision that’s right for you.

What is Sleep Hygiene?

Sleep hygiene refers to the daily habits, environmental factors, and bedtime routines that support healthy, restorative sleep. For the general population, this might include keeping a consistent sleep schedule, limiting caffeine late in the day, and reducing screen time before bed. For trauma survivors and those living with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), sleep hygiene needs to go further, addressing safety, nervous system regulation, and the unique challenges of trauma-related sleep issues.

This may involve creating a safe and calming sleep environment, using grounding techniques to reduce nighttime anxiety, and establishing predictable bedtime rituals that signal to the body it’s safe to rest. When paired with evidence-based PTSD treatment such as cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), imagery rehearsal therapy, or EMDR, trauma-informed sleep hygiene can help rebuild trust in the night and improve overall sleep quality.

Reclaiming the Night: Holistic Sleep Hygiene for Trauma Survivors

Conventional sleep hygiene advice often fails trauma survivors, not because the tips are wrong, but because they lack the safety and nervous system support required for someone with PTSD. Trauma-informed sleep hygiene includes:

Creating a safe sleep environment

(weighted blankets, ambient noise, pets, grounding objects)

Reducing sensory triggers

(minimizing harsh lights, intense screen time, loud noises)

Establishing predictable rituals

(same sleep/wake times, relaxing pre-bed routines, dimming lights)

Avoiding overstimulation at night

(news, social media, caffeine, or emotional conversations)

Supporting parasympathetic activation

(vagus nerve stimulation, gentle yoga, body scans, EMDR calm place exercise)

For first responders, military personnel, and firefighters, these rituals may need to be adapted to night shifts or unpredictable sleep patterns. For survivors of interpersonal trauma, the sleep environment itself may require therapeutic work to feel safe again.

Table: Therapeutic Sleep Intervention Comparisons

Many approaches can improve sleep in people with trauma-related sleep problems, but each works in a different way. This table compares common options, focusing on what they target, their strengths, and their limitations. It’s meant as a quick reference, not a treatment recommendation.

| Intervention | Focus | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CBT-I (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia) | Restructuring sleep-related thoughts and behaviors to improve insomnia. | Evidence-based first-line treatment for insomnia; no medication side effects; adaptable to PTSD. | Requires active participation; can take several weeks; less direct impact on trauma-related nightmares. |

| IRT (Imagery Rehearsal Therapy) | Changing nightmare scripts to reduce frequency and distress. | Targets nightmares directly; can be combined with CBT-I; non-invasive. | Not effective for all types of nightmares; may be less impactful if nightmares are infrequent. |

| EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) | Processing traumatic memories to reduce distress and improve emotional regulation. | Addresses root cause of trauma-related arousal; can indirectly improve sleep quality. | Requires readiness for trauma processing; not designed as a primary insomnia treatment. |

| Medications | Altering brain chemistry to promote sleep or reduce nightmares. | May work quickly; useful when symptoms are severe; can be tailored to specific symptoms (e.g., nightmares). | Possible side effects; may not address underlying trauma; risk of dependence with some sleep aids. |

| Sleep Hygiene | Optimizing daily habits and environment to support healthy sleep patterns. | Low cost; supports other treatments; can improve overall sleep quality. | Often insufficient on its own for trauma-related sleep problems; requires consistency. |

Rest Is Recovery, But It Has to Be Rebuilt

Restful sleep isn't always a passive luxury, for trauma survivors, it often has to be actively rebuilt through behavioral change, trauma processing, and nervous system regulation. Working with a trauma-informed therapist and healthcare providers trained in sleep medicine can help create a treatment plan that addresses both insomnia symptoms and the underlying trauma.

With time, patience, and the right support, the brain can learn to trust the night again, transforming sleep from a place of danger into a foundation for recovery.

If you’ve been looking for a trauma therapist in Austin, TX who can support you holistically while guiding you through trauma-focused therapy, schedule a free 15-minute consultation. I’d be happy to help you explore if EMDR is right for you.

Alex Penrod, MS, LPC, LCDC

Founder & EMDR Therapist | Neuro Nuance Therapy and EMDR, PLLC | Austin, TX

Last Updated October 5, 2025

Disclaimer: This article is meant for educational purposes only. It is not intended to diagnose or treat any condition and should not be taken as medical or clinical advice. Seek the assistance of a medical or clinical professional for more personalized sleep advice.

Frequently Asked Questions

-

After trauma, the nervous system can stay stuck in survival mode, leading to hypervigilance, nightmares, or difficulty falling asleep. The body remains alert even when it’s time to rest, which is why many trauma survivors experience insomnia or restless nights.

-

When you don’t get enough restorative sleep, your brain struggles to regulate emotions and process memories. Sleep loss can intensify anxiety, irritability, and intrusive thoughts, creating a cycle that makes PTSD symptoms harder to manage.

-

Evidence-based approaches like CBT for Insomnia (CBT-I) and Imagery Rehearsal Therapy (IRT) are highly effective for trauma-related sleep issues. Combined with therapies such as EMDR, these treatments help the brain relearn safety around rest and reduce nightmares over time.

-

Yes. EMDR helps the brain reprocess traumatic memories and reduce the body’s threat response, which often leads to calmer nights and fewer sleep disturbances. As the nervous system becomes more regulated, the brain naturally enters deeper, more restorative sleep cycles.

-

Medication can sometimes help in the short term, but lasting improvement comes from treating the root causes of disrupted sleep, trauma, stress, and hyperarousal. Behavioral strategies and trauma-focused therapy build more sustainable and natural sleep patterns.

-

Begin by setting a consistent bedtime, dimming lights an hour before bed, and limiting screens. Gentle movement, mindfulness, or journaling before sleep can signal safety to your nervous system. Healing sleep takes time, progress is gradual, not all at once.

Learn More About Holistic Trauma Recovery

References

Harrington, M. O., Karapanagiotidis, T., Phillips, L., Smallwood, J., Anderson, M. C., & Cairney, S. A. (2025). Memory control deficits in the sleep-deprived human brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 122(1), e2400743122. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2400743122

Koffel, E., Khawaja, I. S., & Germain, A. (2016). Sleep disturbances in posttraumatic stress disorder: Updated review and implications for treatment. Psychiatric Annals, 46(3), 173–176. https://doi.org/10.3928/00485713-20160125-01

Lancel, M., van Marle, H. J. F., Van Veen, M. M., & van Schagen, A. M. (2021). Disturbed sleep in PTSD: Thinking beyond nightmares. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 767760. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.767760

Patel, A. K., Reddy, V., Shumway, K. R., et al. (2025). Physiology, sleep stages. [Updated 2024 Jan 26]. In StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526132/

So, C. J., Miller, K. E., & Gehrman, P. R. (2023). Sleep disturbances associated with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatric Annals, 53(11), 491–495. https://doi.org/10.3928/00485713-20231012-01

Zhang, Y., Ren, R., Sanford, L. D., Yang, L., Zhou, J., Zhang, J., Wing, Y. K., Shi, J., Lu, L., & Tang, X. (2019). Sleep in posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of polysomnographic findings. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 48, 101210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2019.08.004