How to Build Social Support for PTSD Recovery

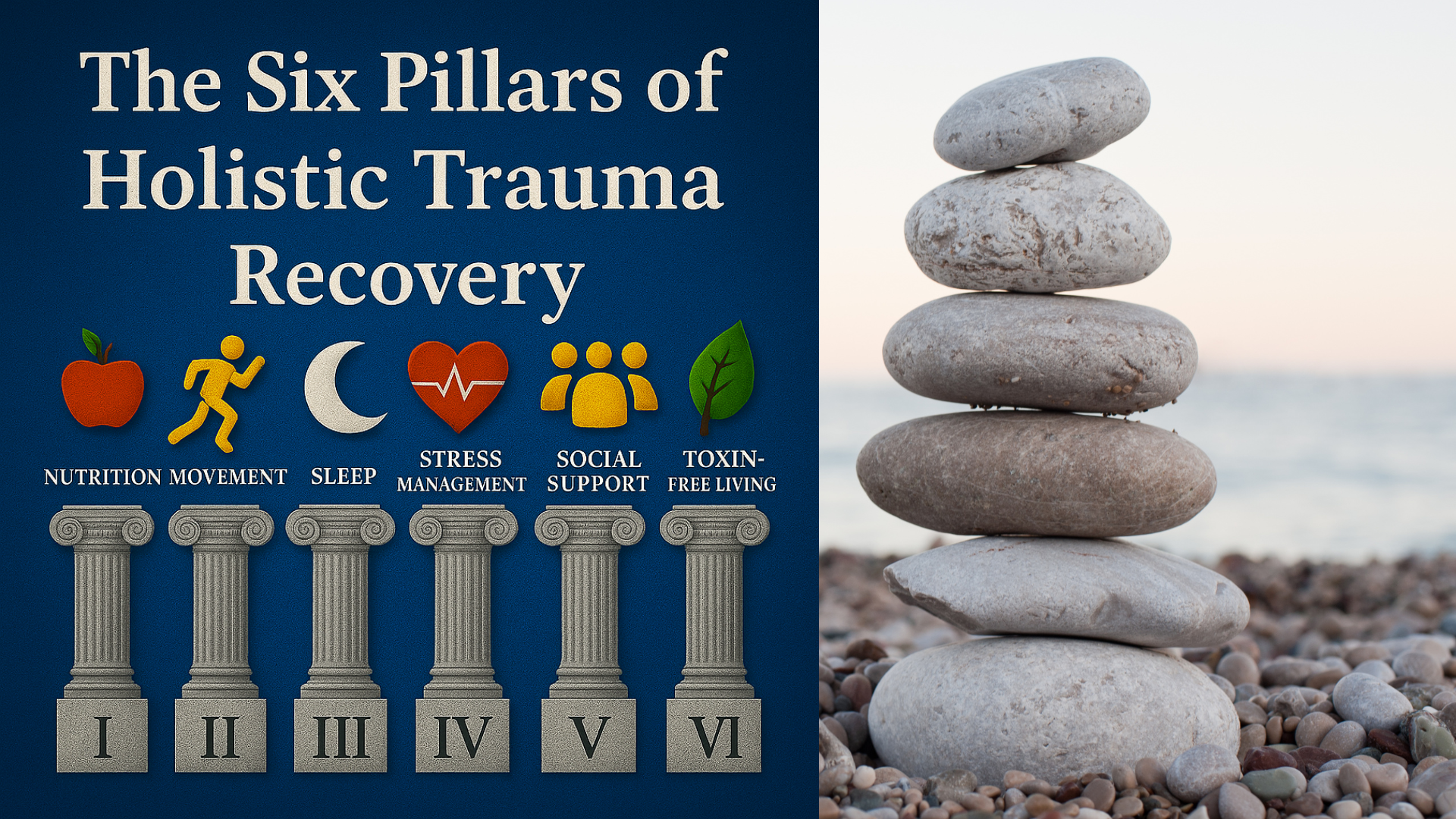

Pillar Five of a Six Pillar Approach

Alex Penrod, MS, LPC, LCDC

EMDR Therapist | Austin, TX

Introduction: Connection as a Healing Force

Human beings are wired for connection. But after traumatic experiences, especially interpersonal trauma like abuse, assault, or betrayal, it’s common to withdraw, isolate, or fear closeness. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5-TR) lists feeling distant or cut-off from other people as a core symptom of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Similarly, the ICD-11 definition of complex PTSD emphasizes persistent negative self-concept and chronic difficulties in relationships. That’s why social support for PTSD recovery is Pillar Five in my six-part series, The Six Pillars of Holistic Trauma Recovery. As an EMDR therapist in Austin, TX, helping my clients develop support outside of sessions is a crucial part of enhancing therapy during sessions.

For trauma survivors, isolation may feel safer in the short term, but over time it reinforces the belief that you have to navigate your pain alone. In contrast, supportive relationships provide a counterbalance to trauma’s core messages of danger, shame, and abandonment. Strong social support is an important factor in trauma recovery, helping to regulate symptoms of PTSD, reduce psychological distress, and improve treatment outcomes.

This article explores how to build social support for PTSD recovery, including: why it matters, how trauma shapes social interactions, and practical strategies for developing a supportive network of loved ones, peers, and professionals.

Table of Contents

Why Social Support Matters in PTSD Recovery

Social support plays a vital role in the recovery process. When we feel seen, heard, and supported in safe relationships, whether by a family member, a support group, or a trauma-informed mental health professional, we restore our capacity for co-regulation. This relational safety calms the stress response, supports emotion regulation, and teaches the brain that not all connection is dangerous. It’s often said that the ability to self-regulate begins with the ability to co-regulate. Think of it like drawing upon a calm nervous system to help yours remember how it feels, or in some cases, learn how it feels for the first time.

Co-regulation and the nervous system

Research in psychotherapy shows that therapeutic presence (the therapist’s attunement, tone of voice, and open posture), communicates safety on a neurophysiological level. This aligns with polyvagal theory which suggests that safety cues engage the vagus nerve and the social engagement system, helping to down-regulate hyperarousal or shutdown states.

More recently, Gernert and colleagues (2023) found that physiological synchrony between therapist and client predicts symptom outcomes. When client and therapist heart rates or arousal levels align in calming states, PTSD symptoms decrease; when they synchronize in distress, symptoms worsen. These findings support what trauma survivors often feel intuitively, supportive relationships literally help regulate the nervous system.

Protective effects across populations

Meta-analyses confirm that higher levels of social support are consistently linked to lower levels of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and better recovery outcomes across trauma types and populations. This includes military veterans, survivors of sexual abuse, survivors of natural disasters, and the general population.

Types of Social Support That Aid Healing

Emotional Support and Safe Relationships

Emotional support, expressed through empathy, compassion, and attentive presence, is a cornerstone of recovery. Family members, intimate partners, and close friends can all provide this, but trauma often complicates these bonds.

Recent evidence suggests that friend support may be particularly protective: in a community study, support from friends predicted recovery more strongly than support from intimate partners or relatives, while PTSD symptom severity predicted later reductions in partner support. This highlights how social interactions can either buffer trauma symptoms or erode under stress.

Loved ones who understand trauma’s effects can offer a stabilizing force. Simple relational gestures such as softened tone, eye contact, or open posture help trauma survivors feel safe enough to reconnect. These small acts are powerful stabilizers that counter social isolation and negative thoughts.

Practical and Community-Based Support

Support also includes practical help and belonging to a social network. Practical help includes having assistance with child care, career development, or daily stressors. Peer support groups, group therapy, and community activities provide structure and shared meaning. For example, veterans often find healing in Department of Veterans Affairs support programs or military peer groups that understand trauma exposure firsthand.

Spiritual communities can also be protective. Varghese, Florentin, & Koola (2021) found that spirituality, gratitude, and meaning-making reduce psychological distress in stressor-related disorders. Participating in religious or spiritual groups provides both social connections and coping mechanisms, reinforcing purpose and belonging. For people with religious trauma this may not be a good fit, but for those who still feel connected with a faith, reconnecting with others in worship can provide a powerful source of support.

Professional and Therapeutic Support

Therapy itself is a form of structured social support. Mental health professionals provide both emotional support and evidence-based treatment options for PTSD.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) help reframe negative thoughts.

Prolonged Exposure Therapy (PE) can reduce avoidance and intrusive thoughts.

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) helps desensitize traumatic memories and reprocess core beliefs maintaining isolation.

Marriage and Family Therapy integrates family members into the recovery process, addressing relationship quality and support roles.

Research shows that professional and non-professional support enhance each other. In veterans receiving Prolonged Exposure Therapy, higher social support in the beginning of treatment predicted greater symptom reduction, and social support increased during treatment. Jarnecke et al. (2022) similarly found that in individuals with co-occurring PTSD and substance use disorders, higher social support was linked with better treatment outcomes.

| Type of Support | Description | Key Benefits | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Support | Empathy, validation, being understood by friends, partners, or loved ones. | Reduces PTSD symptoms, improves emotion regulation, decreases isolation. | Sippel et al., 2024; Fares-Otero et al., 2024 |

| Practical Support | Tangible help (transport, meals, childcare, finances) from family/community. | Buffers daily stress, lowers relapse risk, improves treatment outcomes. | Perry et al., 2023; Thompson-Hollands et al., 2022 |

| Community Support | Belonging in peer groups, support groups, or spiritual communities. | Builds meaning/purpose; decreases depression and loneliness. | Varghese et al., 2021; Fares-Otero et al., 2024 |

| Professional / Therapeutic | CBT, CPT, PE, EMDR, Family Therapy with a trauma-informed clinician. | Co-regulates the nervous system; enhances treatment outcomes. | Geller & Porges, 2014; Gernert et al., 2023; Price et al., 2018; Jarnecke et al., 2022 |

How Trauma Shapes Social Relationships

Trauma doesn't only create distressing memories, it reshapes the way survivors view themselves and others.

PTSD (DSM-5-TR) includes symptoms like detachment, estrangement, and inability to feel close to others.

Complex PTSD (ICD-11) adds persistent negative self-concept, shame, and chronic difficulties in relationships.

Erosion of Support Over Time

Longitudinal studies show that PTSD symptoms often predict declines in perceived support, while higher social support predicts later decreases in PTSD symptoms, a dynamic sometimes called “social erosion.” In a 9/11-exposed cohort, Liu et al. (2022) found this bidirectional pattern held across 14 years. Similarly, Nickerson et al. (2017) reported that trauma symptoms predicted later decreases in support among injury survivors.

Interpersonal Trauma and Betrayal

Survivors of sexual assault, domestic violence, or child abuse often experience betrayal by intimate partners or trusted individuals. Tirone et al. (2021) found that negative social reactions to disclosure of interpersonal trauma predicted greater PTSD severity, showing how harmful responses can intensify symptoms. Not being believed, or being invalidated following trauma can create a secondary trauma adding to distress and loss of trust. The layered nature of interpersonal and complex trauma is a major reason it requires a specialized treatment approach.

Parenting and Family Roles

PTSD also affects the parent-child relationship. Meijer et al. (2023) highlight that trauma symptoms can reduce parenting capacity and disrupt attachment, which in turn undermines family support. These findings reinforce that difficulties in relationships are not incidental but integral to PTSD, and often show up in proportion with symptom severity. Counteracting these effects and rebuilding relationships is crucial.

The Impact of Social Support on PTSD Symptoms

Supportive relationships reduce PTSD symptom severity, improve emotion regulation, and buffer against psychological distress.

Treatment outcomes: Veterans with strong social support respond better to exposure therapy.

Substance use: Among trauma survivors with substance use disorders, higher support predicts better treatment outcomes.

Long-term trajectories: Assault survivors with higher perceived social support reported better PTSD symptom trajectories across eight years.

Veteran populations: Belonging and support predicted lower PTSD severity over time, while PTSD symptoms predicted declines in tangible support.

Together, these findings confirm that support networks are not simply helpful, they are critical in shaping treatment outcomes, physical health, and recovery process.

Barriers and Risk Factors to Social Support

Not all social support is stable or beneficial. Trauma survivors often face barriers:

Negative reactions to trauma disclosure can worsen trauma symptoms.

Declines in partner support when PTSD symptoms increase.

Negative family involvement such as criticism, avoidance, or invalidation can hinder recovery.

Other risk factors include stigma, gender differences in help-seeking, and ongoing stressors such as intimate partner conflict or substance use. Understanding these barriers is essential to tailoring treatment approaches that strengthen, not undermine, support networks.

| Barrier / Risk Factor | Impact on Recovery | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Negative Social Reactions (criticism, disbelief, blame) | Increase PTSD severity; intensify shame and isolation. | Tirone et al., 2021 |

| Declines in Partner Support | PTSD symptoms can erode partner support over time. | Sippel et al., 2024 |

| Negative Family Involvement (invalidation, conflict) | Undermines treatment; perpetuates distress. | Thompson-Hollands et al., 2022 |

| Betrayal Trauma (sexual/domestic violence, child abuse) | Predicts persistent PTSD; damages trust and relational safety. | Tirone et al., 2021; Johansen et al., 2022 |

| Stigma & Gender Differences in Help-Seeking | Reduces willingness to seek care; contributes to untreated symptoms. | Fares-Otero et al., 2024 |

Future Directions and Research on Social Support & PTSD

While evidence strongly supports the role of social support, important gaps remain:

More randomized controlled trials are needed to test interventions that enhance support.

Studies should track longitudinal dynamics of PTSD and support across diverse populations.

More attention to complex PTSD and its relational dimensions is warranted.

Research on parenting, family systems, and intergenerational effects remains limited.

Future research should also investigate digital and online support networks, given their growing role in mental health care.

Building and Strengthening a Support Network

Rebuilding connection after trauma is not easy, but it is possible. Here are practical strategies trauma survivors can use to cultivate a supportive network:

Start with safe people. Identify family members, friends, or peers who feel emotionally safe. Even brief social interactions can act as stabilizers.

Seek professional help. A mental health professional or healthcare provider trained in trauma therapy can help guide recovery and foster social reconnection.

Join structured groups. Peer support groups, group therapy, and spiritual or community organizations provide belonging and accountability.

Practice gratitude and meaning-making. Research shows that gratitude and purpose reduce loneliness and depression in trauma survivors.

Educate your network. Family therapy and psychoeducation can teach loved ones how to provide supportive responses.

Recovery is often nonlinear, but building social connections, even small ones, gradually counteracts avoidance and isolation.

How to Build a Support System with REACH

Information is helpful, but recovery requires action. That’s where the REACH framework comes in: a simple five-step strategy for developing a trauma-informed support system.

R — Review

Start by reviewing your current resources. Who do you already have in your corner? Family, friends, peers, or professionals? Make a list and note how each connection feels: safe, neutral, or draining. This step clarifies where you stand.

E — Evaluate

Next, evaluate your areas of need. Do you need more emotional support, practical help, community belonging, or professional guidance? Identifying gaps prevents over-reliance on one person and highlights the kinds of support that would make the biggest difference.

A — Activate

Healing begins with small, safe steps. Activate one connection this week: send a text to a trusted friend, RSVP to a peer support group, or schedule a session with a mental health professional. Taking one specific action breaks through isolation and builds momentum.

C — Connect

Then, connect more broadly. Trauma recovery is strongest when support is diverse: friends who listen, community groups that foster belonging, therapy that provides professional guidance. Regular, low-stakes touchpoints, like a weekly walk, a standing call, or a group meeting, help make support a steady part of life.

H — Hone

Finally, hone your network by running regular check-ins. Ask yourself: What’s helping me? What’s draining? What do I need next? Keep what strengthens your recovery, let go of what harms, and set one new goal for the next month.

REACH offers both structure and flexibility. You don’t have to transform your entire social world at once, just begin with what feels safe and build from there. Over time, these intentional steps replace isolation with connection, giving you a support system that sustains long-term recovery.

Taking the Next Step: Getting Help

Building a support network takes time, but you don’t have to do it alone. If you are struggling with posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms or complex trauma, reaching out to a mental health professional is a vital step.

Visit the National Center for PTSD for resources and educational materials.

If you’re a veteran, the Department of Veterans Affairs and Veterans Health and Wellness Foundation offer specialized resources and health services.

If you’ve experienced domestic violence or sexual abuse, organizations exist to provide immediate support and safe connection. For local options in Austin, visit my local resources article Healing Trauma the Austin Way: How Holistic Living Supports EMDR Therapy.

At Neuro Nuance Therapy and EMDR, PLLC, I specialize in EMDR therapy and trauma-focused care, integrating holistic strategies and evidence-based treatment approaches. I’m a firm believer that strong social support is not only an important factor in healing, it’s the foundation of long-term trauma recovery. Schedule a free 15-minute consultation to learn more about integrating specialized trauma therapy into your healing process.

Alex Penrod, MS, LPC, LCDC

EMDR Therapist | Austin, TX

Disclaimer: This article is meant for educational purposes only. It is not intended to diagnose or treat any condition and should not be taken as medical or clinical advice. Seek the assistance of a medical or clinical professional for more personalized information.

Last Updated October 5, 2025

Learn More About Holistic Trauma Recovery

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Fares-Otero, N. E., Pfaltz, M. C., Elbert, T., Wilker, S., Kolassa, I.-T., & Morina, N. (2024). Social support and (complex) posttraumatic stress: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 15(1), 2398921. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008066.2024.2398921

Geller, S. M., & Porges, S. W. (2014). Therapeutic presence: Neurophysiological mechanisms mediating feeling safe in therapeutic relationships. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 24(3), 178–192. (No DOI) https://www.sharigeller.ca/_images/pdfs/TP_and_PVT_for_print.pdf

Gernert, C. C., Nelson, A., Falkai, P., & Falter-Wagner, C. M. (2023). Synchrony in psychotherapy: High physiological positive concordance predicts symptom reduction and negative concordance predicts symptom aggravation. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 32(1), e1978. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1978

Jarnecke, A. M., Saraiya, T. C., Brown, D. G., Richardson, J., Killeen, T., & Back, S. E. (2022). Examining the role of social support in treatment for co-occurring substance use disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 15, 100427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2022.100427

Johansen, V. A., Milde, A. M., Nilsen, R. M., Breivik, K., Nordanger, D. Ø., Stormark, K. M., & Weisæth, L. (2022). The relationship between perceived social support and PTSD symptoms after exposure to physical assault: An eight-year longitudinal study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(9–10), NP7679–NP7706. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520970314

Liu, S. Y., Li, J., Leon, L. F., Schwarzer, R., & Cone, J. E. (2022). The bidirectional relationship between posttraumatic stress symptoms and social support in a 9/11-exposed cohort: A longitudinal cross-lagged analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2604. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052604

Meijer, L., Franz, M. R., Deković, M., van Ee, E., Finkenauer, C., Kleber, R. J., van de Putte, E. M., & Thomaes, K. (2023). Towards a more comprehensive understanding of PTSD and parenting. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 127, 152423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2023.152423

Nickerson, A., Creamer, M., Forbes, D., McFarlane, A. C., O’Donnell, M. L., Silove, D., Steel, Z., Felmingham, K., Hadzi-Pavlovic, D., & Bryant, R. A. (2017). The longitudinal relationship between post-traumatic stress disorder and perceived social support in survivors of traumatic injury. Psychological Medicine, 47(1), 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716002361

Perry, N. S., Goetz, D. B., & Shea, M. T. (2023). Longitudinal associations of PTSD and social support by support functions among returning veterans. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 15(8), 1346–1354. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001190

Price, M., Lancaster, C. L., Gros, D. F., Legrand, A. C., van Stolk-Cooke, K., & Acierno, R. (2018). An examination of social support and PTSD treatment response during prolonged exposure. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 81(3), 258–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.2017.1402569

Sippel, L. M., Liebman, R. E., Schäfer, S. K., Ennis, N., Mattern, A. C., Rozek, D. C., & Monson, C. M. (2024). Sources of social support and trauma recovery: Evidence for bidirectional associations from a recently trauma-exposed community sample. Behavioral Sciences, 14(4), 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14040284

Thompson-Hollands, J., Chinman, M., Rosen, C. S., Cook, J. M., Enders, B., Miller, C. J., & Spoont, M. R. (2022). Family involvement in PTSD treatment: Perspectives from a nationwide sample of Veterans Health Administration clinicians. Psychological Services, 19(3), 585–595. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000631

Tirone, V., Orlowska, D., Lofgreen, A. M., Blais, R. K., Stevens, N. R., Klassen, B., Held, P., & Zalta, A. K. (2021). The association between social support and posttraumatic stress symptoms among survivors of betrayal trauma: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1883925. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.1883925

Varghese, S. P., Florentin, O. D., & Koola, M. M. (2021). Role of spirituality in the management of major depression and stress-related disorders. Chronic Stress, 5, 2470547020971232. https://doi.org/10.1177/2470547020971232

World Health Organization. (2024). Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): Fact sheet. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/post-traumatic-stress-disorder

Frequently Asked Questions

Supportive relationships help calm your nervous system, offer co-regulation, and counteract isolation. This relational safety strengthens emotional resilience and is linked with better treatment outcomes.

Emotional support (empathy, validation), practical support (help with tasks, resources), community or peer support groups, and professional/therapeutic support all play complementary roles.

Trauma can lead to withdrawal, fear of closeness, mistrust, and relationship difficulties. Over time, symptoms may erode perceived support, creating a cycle of isolation.

Use the REACH method:

Review your existing connections and how safe they feel

Evaluate what types of support you need

Activate a small, safe connection (send a message, attend a group)

Connect more broadly to varied supports

Hone the network by checking what works or drains you

Barriers include negative reactions when sharing trauma, invalidation or betrayal, declining support as PTSD symptoms rise, and stigma or shame about seeking help.

Absolutely. Therapy provides structured healing and co-regulation, while peer or community connections offer ongoing emotional and relational support between sessions. Together they reinforce recovery.