Exercise and PTSD Recovery: Pillar Two of a Six Pillar Approach

Alex Penrod, MS, LPC, LCDC

Founder & EMDR Therapist | Austin, TX

Reclaiming the Body Through Movement

When we think of trauma recovery, physical exercise isn’t always the first thing that comes to mind. But for survivors of traumatic events, movement can become a powerful tool for healing. Trauma can involve living through abuse, war, a natural disaster, or the tragic loss of a loved one, and these experiences can reshape the brain and body in profound ways. Trauma-focused psychotherapies are the gold standard for PTSD treatment. However, research continues to affirm that movement helps people re-regulate, reconnect, and rebuild.

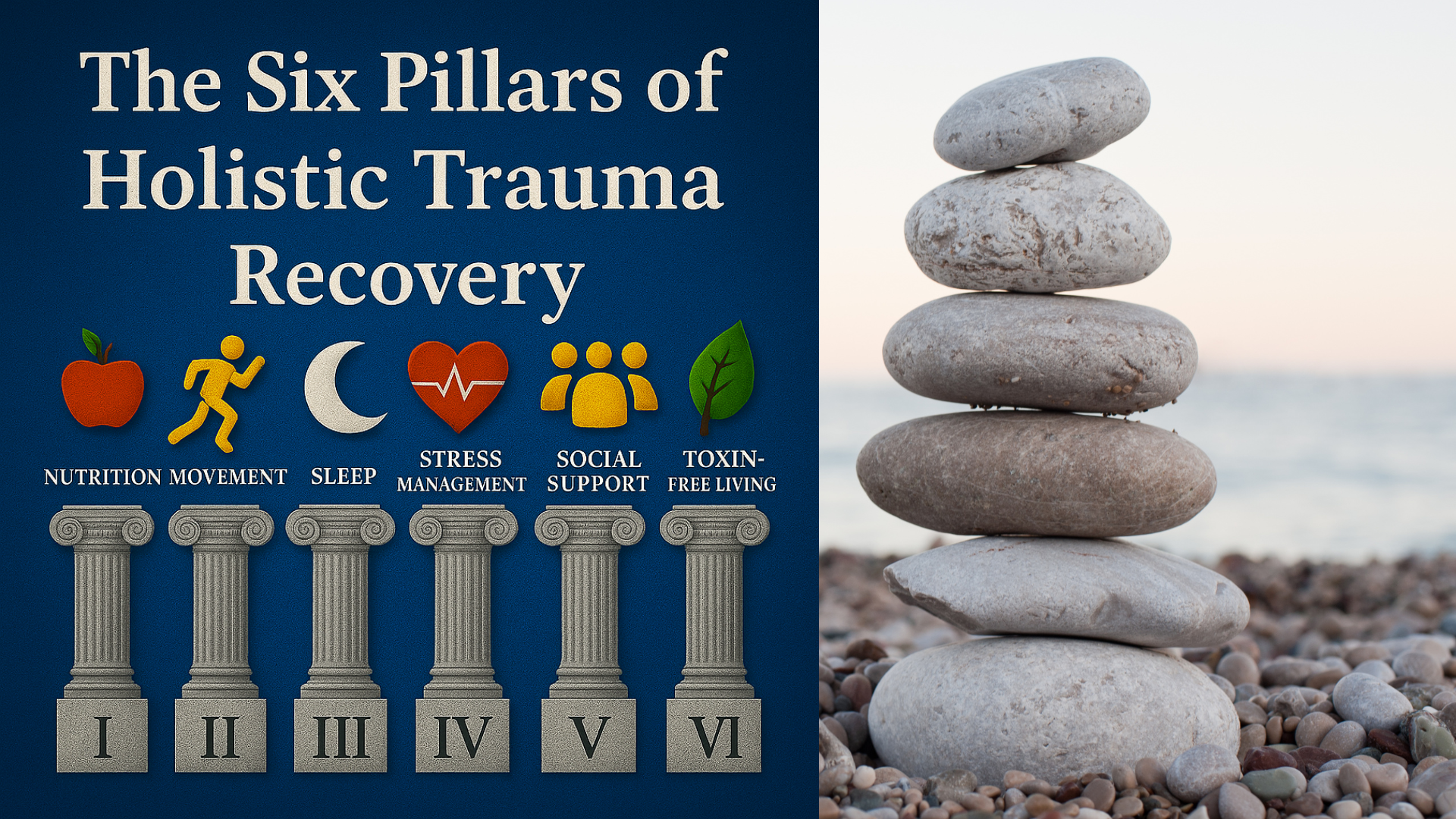

Exercise is Pillar Two in The Six Pillars of Holistic Trauma Recovery, a framework I use at Neuro Nuance Therapy and EMDR, PLLC to help clients reclaim a sense of agency over their healing and prepare for EMDR therapy. My approach is inspired by the work of Sugden and Merlo (2024) and their fantastic article on healing the gut-brain microbiota using the six pillars of lifestyle psychiatry. In this article, we’ll explore the beneficial effects of exercise on posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, the science behind why it works, and how to create a trauma-informed approach to movement that supports trauma-focused therapies like EMDR, CBT, or exposure therapy.

Table of Contents

How Trauma Affects the Body and Brain

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR) as a trauma- and stressor-related disorder. But while it’s often categorized as a mental health condition, its effects are physical, neurobiological, and behavioral as well.

Exposure to a traumatic event can alter the brain regions responsible for memory, threat detection, and emotional regulation: specifically the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex. Trauma can also have downstream effects of the body's stress response system, which often show up as secondary health problems.

Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder often include:

Hyperarousal and exaggerated startle responses

Disrupted sleep quality

Chronic muscle tension or fatigue

Hormonal imbalances and immune suppression

Reduced heart rate variability

Gastrointestinal distress

Heightened anxiety symptoms and depressive symptoms

Increased risk for substance use disorders and comorbid physical illnesses

For those with Complex PTSD, the effects may be even more systemic, impacting attachment, identity, and emotion regulation over time.

Why Movement Helps People during PTSD Treatment

The benefits of exercise for trauma survivors go far beyond just “feeling better.” Regular movement, as described in observational studies, pilot studies, and narrative reviews, shows potential to reduce the severity of PTSD symptoms, enhance cognitive performance, and improve overall functioning.

There are many potential mechanisms behind the impact of movement. Here’s how exercise can support trauma recovery at multiple levels:

1. Neuroplasticity and Brain Health

Physical activity increases brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein that supports neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to rewire itself. This is essential for facilitating and enhancing memory reconsolidation in the hippocampus. Trauma-focused therapies like EMDR rely on neuroplasticity and memory reconsolidation to reprocess traumatic memories.

2. Autonomic Nervous System Regulation

Exercise improves vagal tone and heart rate variability, helping shift the body out of survival mode. It enhances parasympathetic activity, calming the fight-flight-freeze response that often defines a trauma survivor's nervous system.

3. Inflammation and Immune System Support

Chronic inflammation plays a crucial role in trauma-related illness. Movement helps reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines, supports immune resilience, and decreases the physical burden of unresolved stress.

4. Hormonal Balancing

Exercise stabilizes stress-related hormones like cortisol, adrenaline, serotonin, and dopamine. These hormonal shifts can support emotional regulation and stabilize mood swings in people recovering from trauma.

5. Behavioral Activation

Avoidance is a key part of PTSD, especially when it comes to physical cues of anxiety. Exercise gradually reintroduces safe body-based activation, counteracting fear conditioning through exposure and mastery.

What Does the Research Say about Exercise for PTSD Recovery?

A search of Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Open Access journals shows the evidence is limited but these are some of the top studies supporting the effect of exercise on PTSD.

Table: Research on Exercise & Physical Activity for PTSD

Below is a summary of peer-reviewed studies examining the effects of exercise and physical activity interventions on PTSD symptoms. Titles link directly to the original publications so you can review the full text or abstracts.

| Study Title (With Link) | General Findings |

|---|---|

| Physical activity in the treatment of Post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis | This meta-analysis found that physical activity significantly reduced PTSD symptoms in military populations, with moderate effect sizes across interventions. |

| Is exercise/physical activity effective at reducing symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in adults — A systematic review | This systematic review found that individual types of exercise have some effect on PTSD symptoms but the greatest effects were observed when different types of exercise were combined 3 times per week, for 30-60 minutes. |

| Yoga for veterans with PTSD: Cognitive functioning, mental health, and salivary cortisol | This pilot study found that yoga was significantly correlated with improved impulse control, sleep, and quality of life, as well as reduced PTSD and depression symptoms in Veterans with PTSD. |

| Emotion dysregulation and heart rate variability improve in US veterans undergoing treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder: Secondary exploratory analyses from a randomised controlled trial | This randomized controlled trial among US Veterans found that a breathing based yoga intervention improved emotion regulation as effectively as Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) and improved heart-rate variability in ways CPT did not. |

| Efficacy of yoga for post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials | This systematic review and meta-analysis found that yoga was associated with significant reductions in self-reported PTSD symptoms, but not in clinician rated PTSD symptoms. Furthermore, the effects of yoga appeared to wane over time and were not significant at follow-up. Decreases in depression were shown to be more durable. |

Forms of Movement That Help People Heal

There’s no one-size-fits-all treatment of PTSD. The best exercise is the one that fits your body, your history, and your healing timeline. The standard treatment protocols focus on therapy and medication and don’t always include movement, but increasingly, they should. The research suggests that no one type of exercise has the monopoly on benefits, and an integrative exercise, or “multi-modal approach” is often helpful.

Here are some trauma-informed forms of exercise:

1. Mind-Body Exercises: Yoga, Tai Chi, and Breathing Exercises

Gentle, movement-based practices are especially useful for clients with Complex PTSD. They strengthen interoception (awareness of internal cues), increase emotion-regulation, and help people feel safer inside their bodies. Breathing exercises can help reduce anxiety and hyperarousal but are sometimes difficult for those with C-PTSD and require a trauma-informed approach to developing the practice. Trauma-informed yoga is becoming increasing popular and would be a good place to start.

2. Resistance Training and Strength-Based Movement

Strength training helps trauma survivors reconnect with their physical power. It builds confidence, increases physical fitness, and improves cognitive function. In one control trial, resistance training outperformed usual care in reducing PTSD symptoms. Strength training often involves intense mind-body connection and controlled activation of the nervous system, which may cultivate a sense of embodied control vs helplessness over physical symptoms. Personally, I find I’m never more present moment focused than I am with an Olympic barbell on my back.

Strength training may be especially useful for trauma survivors recovering from physical assault, chronic disempowerment, or depressive shutdown.

3. Cardiovascular and Aerobic Activity

Running, biking, hiking, and swimming can improve sleep quality, cognitive clarity, and immune function. For military veterans, Veterans group exercise programs are increasingly integrated into trauma treatment according to journals like Military Medicine and organizations like the the Department of Veterans Affairs.

These programs often report improved primary outcome measures like reduced PCL-5 (PTSD symptoms) scores, and better secondary outcomes such as emotion regulation and social connection.

Integrating Exercise Into Trauma Therapy

While movement is not a replacement for therapy, it can significantly enhance traditional cognitive behavioral therapy, exposure therapy, and EMDR therapy. Many trauma therapists are beginning to view exercise as part of an expanded toolkit for healing.

At Neuro Nuance Therapy and EMDR, PLLC, I help people integrate movement in ways that support their current phase of therapy and improve quality of life.

Here’s how to begin:

Step 1: Start Small

Begin with 5–10 minutes of gentle movement. This could be stretching, a walk around the block, or basic breathing exercise work. The goal is to rebuild trust with the body, not to “push through” anything.

Step 2: Reflect and Adjust

Track how your system responds: Did you feel grounded afterward? Was sleep easier? Did session work feel more manageable? This is how movement becomes a co-regulator.

Step 3: Personalize

Try different types of exercise, some clients gravitate toward resistance work, others prefer yoga, long walks, or more intense cardio. Let your system tell you what feels supportive.

Step 4: Integrate With Therapy

Use physical activity before or after therapy to help stabilize your mood and nervous system. For clients undergoing EMDR, movement between sessions can assist with regulation and memory consolidation. I'll never forget how I felt during a workout after completing my first memory target in EMDR. The weight was moving with ease and I could tell my nervous system was carrying less of my past.

Cautions and Considerations

Exercise can be challenging for those with a history of body shame, injury, chronic pain, or disordered eating. In some cases, exercise itself may have been used in compulsive or punitive ways in the past.

If this applies to you, work with a trauma-informed provider, ideally a therapist and/or healthcare professional who understands how to help people reconnect with their bodies gently.

Avoid rigid routines, self-judgment, or perfectionism. The goal is not to fix yourself. It’s to feel safe enough to move forward.

Reframing the Role of Exercise in Trauma Recovery

Traditional models of trauma therapy focused heavily on talk therapy and medication. Today, more clinicians are embracing integrative care, especially in the treatment of PTSD.

Still, there are gaps:

Most studies rely on specific populations (e.g. military veterans)

More research is needed for clients with Complex PTSD, childhood trauma, or multiple diagnoses

Guidelines don’t yet fully address optimal type of exercise, dosage, duration, or adaptation across different bodies and histories

Although there are many one off pilot studies, there needs to be more randomized controlled trials to solidify what seems to be an intuitive notion into a standard of care.

But the momentum is building. As clients, clinicians, and systems evolve, movement is gaining recognition not as a side benefit, but as a foundational practice for mental, physical, and relational healing. My clients often report on the benefits they experience from exercise and movement sometimes becomes a cornerstone of their recovery lifestyle.

Final Thoughts: Reclaim Your Body as an Ally

Trauma can make your own body feel like the enemy. But movement, done with care, intention, and trauma-informed awareness, can help reclaim that space. Consistency and regular exercise is more important than intensity, in fact too much intensity may become too taxing and start to decrease the positive effects. It's not about perfection or winning a competition, It’s about building capacity, restoring connection, and honoring your system’s resilience.

Whether you're a Veteran coping with hypervigilance, a survivor of a natural disaster, or someone healing from chronic stress, movement can meet you where you are.

With the right support, physical exercise becomes a ritual of return: to your body, your rhythm, and your life.

Neuro Nuance Therapy and EMDR, PLLC | Austin, TX

Last Updated October 5, 2025

Disclaimer: This article is meant for educational purposes only. It is not intended to diagnose or treat any condition and should not be taken as medical or clinical advice. Seek the assistance of a medical or clinical professional for more personalized physical fitness advice.

Frequently Asked Questions

-

Exercise helps regulate the nervous system, reduce inflammation, and support neuroplasticity. Movement restores a sense of safety in the body and complements trauma-focused therapy like EMDR by grounding emotional healing in physical regulation.

-

Physical activity boosts brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), balances stress hormones, and promotes healthy neurotransmitter function, all essential for trauma recovery and improved mood stability.

-

Gentle, trauma-informed movement such as yoga, walking, strength training, or swimming works best. These activities build interoceptive awareness, body trust, and emotional resilience without overwhelming the nervous system.

-

Begin small, five minutes of stretching or a short walk is enough. Focus on consistency, curiosity, and comfort rather than intensity. Progress gradually to rebuild safety in your body.

-

Yes. Overexertion or perfectionistic exercise can trigger stress responses. Choose mindful, body-aware movement and consult trauma-informed professionals if exercise feels compulsive or dysregulating.

-

No. Movement supports therapy but does not replace it. Exercise enhances EMDR, CBT, and other trauma-focused treatments by strengthening the body-mind connection and improving stress regulation.

Learn More About Holistic Trauma Recovery

References

Goldstein, L. A., Mehling, W. E., Metzler, T. J., Cohen, B. E., Barnes, D. E., Choucroun, G. J., Silver, A., Talbot, L. S., Maguen, S., Hlavin, J. A., Chesney, M. A., & Neylan, T. C. (2018). Veterans Group Exercise: A randomized pilot trial of an Integrative Exercise program for veterans with posttraumatic stress. Journal of Affective Disorders, 227, 345–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.002

Hegberg, N. J., Hayes, J. P., & Hayes, S. M. (2019). Exercise intervention in PTSD: A narrative review and rationale for implementation. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 133. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00133

Jadhakhan, F., Lambert, N., Middlebrook, N., Evans, D. W., & Falla, D. (2022). Is exercise/physical activity effective at reducing symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in adults - A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 943479. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.943479

Mathersul, D. C., Dixit, K., Schulz-Heik, R. J., Avery, T. J., Zeitzer, J. M., & Bayley, P. J. (2022). Emotion dysregulation and heart rate variability improve in US veterans undergoing treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder: Secondary exploratory analyses from a randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1), 268. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-03886-3

Nejadghaderi, S. A., Mousavi, S. E., Fazlollahi, A., Motlagh Asghari, K., & Garfin, D. R. (2024). Efficacy of yoga for posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychiatry Research, 340, 116098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2024.116098

Rosenbaum, S., Sherrington, C., & Tiedemann, A. (2015). Exercise augmentation compared with usual care for post-traumatic stress disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 131(5), 350–359. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12371

Rosenbaum, S., Vancampfort, D., Steel, Z., Newby, J., Ward, P. B., & Stubbs, B. (2015). Physical activity in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 230(2), 130–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.10.017

Zaccari, B., Callahan, M. L., Storzbach, D., McFarlane, N., Hudson, R., & Loftis, J. M. (2020). Yoga for veterans with PTSD: Cognitive functioning, mental health, and salivary cortisol. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(8), 913–917. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000909